Perhaps some of the readers have already heard about Centrifugo before. This article will focus on the development of the second version of the server and the new real-time library for the Go language, which is its basis.

My name is Alexander Emelin. Last summer, I joined the Avito team, where I am now helping to develop the Avito Messenger backend. New work directly related to fast message delivery to users, and new colleagues inspired me to continue working on the open-source project Centrifugo.

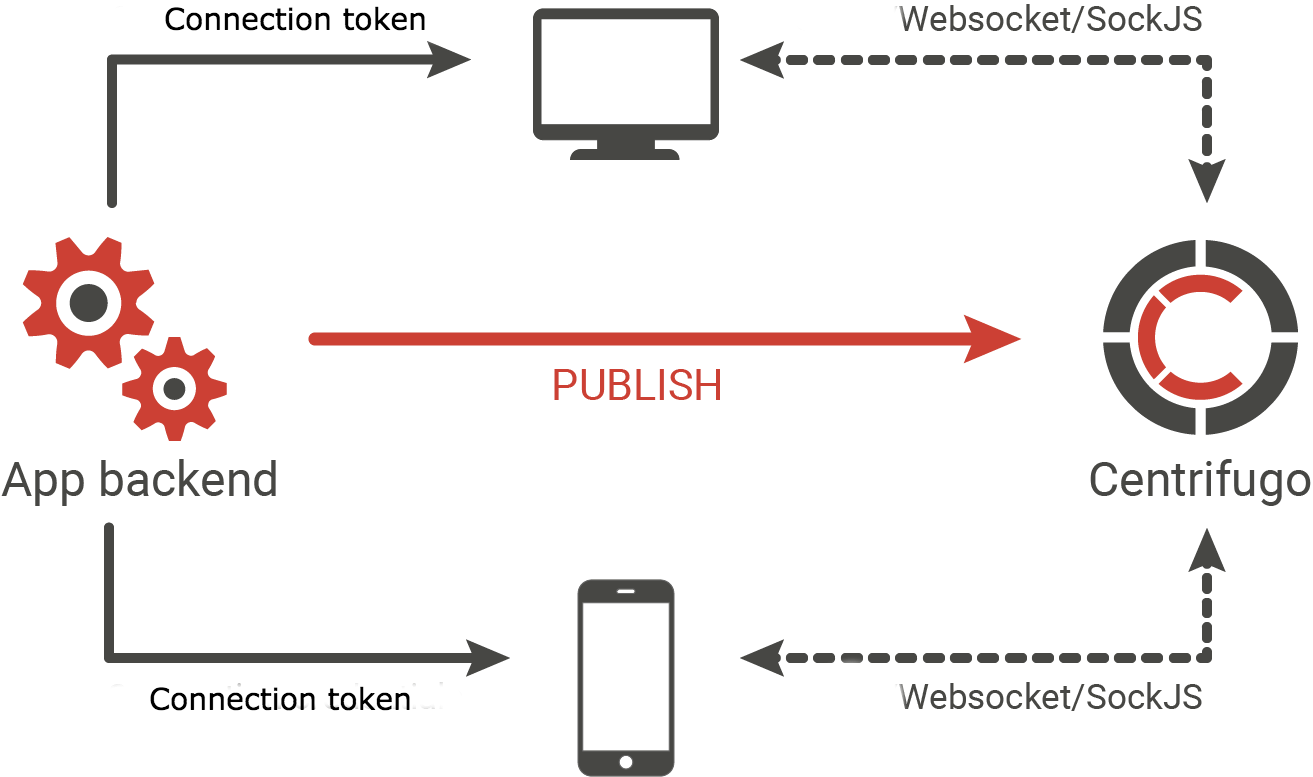

In a nutshell, this is a server that takes on the task of keeping persistent connections from users of your application. Websocket or SockJS polyfill is used as a transport, which can, if it is impossible to establish a Websocket connection, work through ventsource, XHR-streaming, long-polling and other HTTP-based transports. Clients subscribe to channels in which the backend via the Centrifuge API publishes new messages as they arise — after which messages are delivered to users subscribed to the channel. In other words - this is a PUB / SUB server.

Currently, the server is used in a fairly large number of projects. Among them, for example, some Mail.Ru projects (intranets, Technopark / Technosphere training platforms, Certification Center, etc.), with the help of Centrifugo, a beautiful dashboard works at the reception in the Badoo Moscow office, and 350,000 users are connected at the spot.im service to the centrifuge.

A few links to previous articles on the server and its application for those who first hear about the project:

I started working on the second version in December last year and continue to this day. Let's see what happens. I am writing this article not only to somehow popularize the project, but also to get a little more constructive feedback before the release of Centrifugo v2 - now there is room for maneuver and backward incompatible changes.

Real-time library for Go

In the Go community from time to time the question arises - are there any alternatives to socket.io on Go? Sometimes I noticed how the developers, in response to this, advised to look towards Centrifugo. However, Centrifugo is a self-hosted server, not a library - the comparison is not fair. I was also asked several times whether it was possible to reuse Centrifugo code in order to write real-time applications in the Go language. And the answer was: it is theoretically possible, but at my own risk and risk - I could not guarantee the backward compatibility of the API of internal packages. It is clear that there is no particular risk to give anyone any reason, but forking is also an option for itself. Plus, I would not say that the API for internal packages was prepared for this use at all.

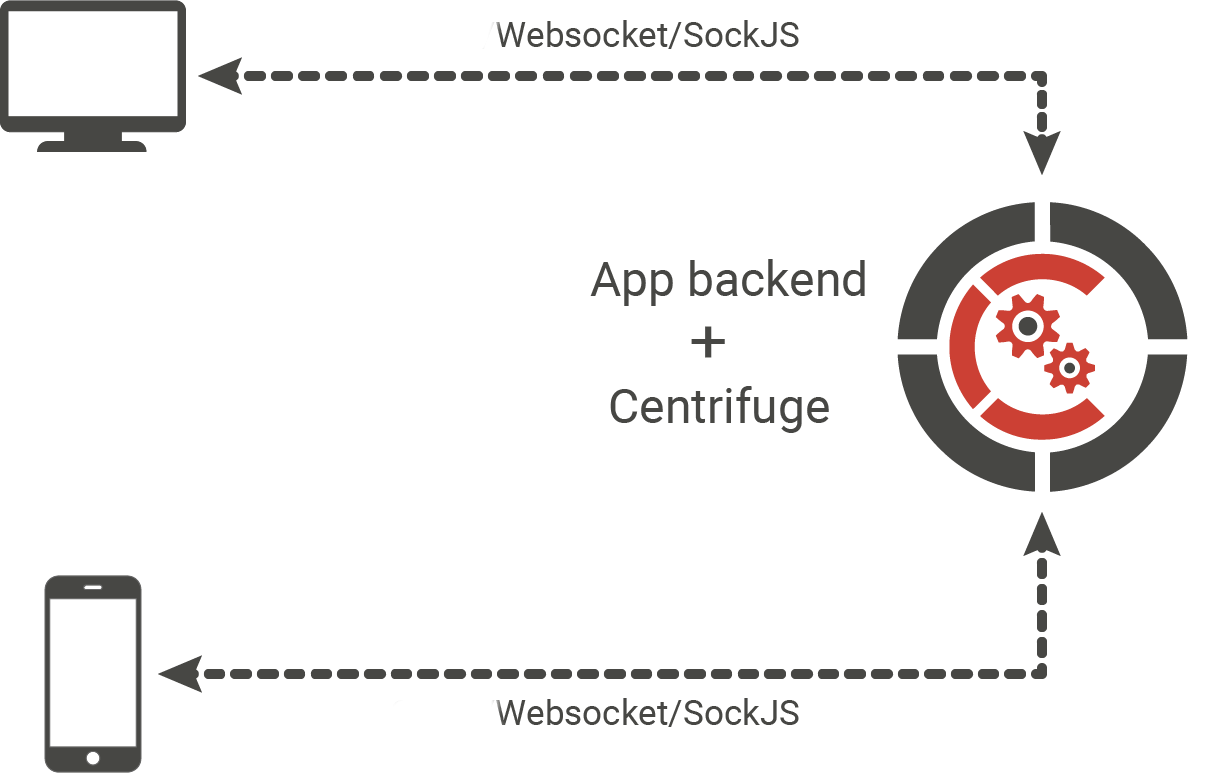

Therefore, one of the ambitious tasks that I wanted to solve in the process of working on the second version of the server is to try to allocate the server core into a separate Go library. I believe that it makes sense, considering how many features the Centrifuge has in order to be adapted to production. There are many features out of the box that are designed to help build scalable real-time applications, removing from the developer the need to write your own solution. I wrote about these features earlier and will outline some of them below.

I will try to justify one more plus of the existence of such a library. Most Centrifugo users are developers who write backend in languages / frameworks with weak concurrency support (for example, Django / Flask / Laravel / ...): to work with a large number of persistent connections if it is possible, in an unobvious or inefficient way. Accordingly, to help with the development of the server, written on Go, not all users can (trite because of the lack of knowledge of the language). Therefore, even a very small community of Go-developers around the library will be able to help in the development of the Centrifugo server using it.

The result was the Centrifuge library. This is still WIP, but absolutely all the features stated in the Github description are implemented and working. Since the library provides a fairly rich API, before guaranteeing backward compatibility, I would like to hear about several successful examples of use in real Go projects. There is no such. As well as unsuccessful :). There are none.

I understand that by naming a library in almost the same way as a server, I will always deal with confusion. But I think this is the right choice, as clients (such as centrifuge-js, centrifuge-go) work with both the Centrifugo library and Centrifugo server. Plus, the name is already firmly established in the minds of users, and I don’t want to lose these associations. And yet, for a little more clarity, I will clarify once again:

- Centrifuge - the Go language library,

- Centrifugo is a turnkey solution, a separate service, which in version 2 will be built on the Centrifuge library.

Centrifugo due to its design (a separate service, not knowing anything about your backend) assumes that the flow of messages via real-time transport will go from the server to the client. What is meant? If, for example, a user writes a message to a chat, you must first send this message to the backend application (for example, AJAX in the browser), check it on the backend side, save it to the database if necessary, and then send it to the Centrifuge API. The library removes this restriction, allowing to organize bidirectional exchange of asynchronous messages between the server and the client, as well as RPC calls.

Let's look at a simple example: we are implementing a small server on Go using the Centrifuge library. The server will receive messages from browser clients via Websocket, the client will have a text box in which you can type a message, press Enter - and the message will be sent to all users subscribed to the channel. That is the most simplified version of the chat. It seemed to me that it would be most convenient to place it in the form of a gist .

You can run as usual:

git clone https:

And then go to http: // localhost: 8000 , open several browser tabs.

As you can see, the entry point to the business logic of the application occurs when hanging On().Connect() callback functions:

node.On().Connect(func(ctx context.Context, client *centrifuge.Client, e centrifuge.ConnectEvent) centrifuge.ConnectReply { client.On().Disconnect(func(e centrifuge.DisconnectEvent) centrifuge.DisconnectReply { log.Printf("client disconnected") return centrifuge.DisconnectReply{} }) log.Printf("client connected via %s", client.Transport().Name()) return centrifuge.ConnectReply{} })

The approach based on callback functions seemed to me most convenient for interacting with the library. Plus, similar, only weakly typed, the approach is used in the implementation of the socket-io server on Go . If suddenly you have thoughts about how the API could be made more idiomatic - I will be glad to hear.

This is a very simple example that does not demonstrate all the capabilities of a library. Some may note that for such purposes it is easier to get a library to work with Websocket. For example, Gorilla Websocket. This is actually the case. However, even in this case, you will have to copy a decent piece of server code from the example in the Gorilla Websocket repository. What if:

- you need to scale the application to multiple machines,

- or you need more than one common channel, but several - and users can dynamically subscribe and unsubscribe from them as you navigate through your application,

- or you need to work when a Websocket-connection failed to establish (there is no support in the client browser, there is a browser extension, some proxy in the path between the client and the server cuts the connection),

- or you need to restore messages that were missed by the client during short breaks of the Internet connection without loading the main database,

- or you need to control the authorization of the user in the channel,

- or you need to disconnect the persistent connection from users who have been deactivated in the application,

- or need information about who is currently present in the channel or events that someone has subscribed / unsubscribed from the channel,

- or need metrics and monitoring?

The Centrifuge library can help you with this - in fact, it inherited all the main features that were previously available in Centrifugo. More examples showing the points stated above can be found on Github .

The strong legacy of Centrifugo can be a disadvantage, as the library has adopted all the server mechanics, which is quite distinctive and, perhaps, may seem unclear to someone or overloaded with unnecessary features. I tried to organize the code in such a way that unused features had no effect on the overall performance.

There are some optimizations in the library that allow more efficient use of resources. This combines several messages into one Websocket frame to save on Write system calls or, for example, using Gogoprotobuf to serialize Protobuf messages and others. Speaking of Protobuf.

Binary Protobuf Protocol

I really wanted Centrifugo to work with binary data ( and not only me ), so in the new version I wanted to add a binary protocol besides the one based on JSON. Now the whole protocol is described in the form of a Protobuf-scheme . This allowed to make it more structured, to rethink some non-obvious solutions in the protocol of the first version.

I think you don’t need to tell for a long time what advantages Protobuf has over JSON - compactness, serialization speed, circuit severity. There is a drawback in the form of unreadability, but now users have the opportunity to decide what is more important for them in a given situation.

In general, traffic generated by the Centrifugo protocol when using Protobuf instead of JSON should decrease by ~ 2 times (excluding application data). In the same ~ 2 times, the CPU consumption in my synthetic load tests decreased as compared to JSON. Actually, these numbers say little, in practice everything will depend on the load profile of a particular application.

For the sake of interest, I launched on a machine with Debian 9.4 and 32 Intel® Xeon® Platinum 8168 CPU @ 2.70GHz vCPU benchmark, which made it possible to compare the bandwidth of client-server interaction in the case of using the JSON protocol and the Protobuf protocol. There were 1000 subscribers to 1 channel. Messages were posted to this channel in 4 streams and delivered to all subscribers. The size of each message was 128 bytes.

Results for JSON:

$ go run main.go -s ws:

Results for the Protobuf case:

$ go run main.go -s ws:

You may notice that the bandwidth of such an installation is more than 2 times greater in the case of Protobuf. The client script can be found here - this is the Nats benchmark script adapted for the realities of Centrifuge .

It is also worth noting that the JSON serialization performance on the server can be “pumped out” using the same approach as in gogoprotobuf — buffer pool and code generation — currently JSON is serialized by the package from the standard Go library built on reflect. For example, in Centrifugo, the first version of JSON is serialized manually using a buffer pool library . Something similar can be done in the future in the second version.

It is worth emphasizing that protobuf can also be used when communicating with the server from a browser. The javascript client uses the protobuf.js library for this. Since the protobufjs library is quite heavy, and the number of users of the binary format will be small, using the webpack and its tree shaking algorithm we generate two versions of the client — one with JSON protocol support and the other with support for both JSON and protobuf. For other environments where the size of resources does not play such a critical role, customers may not worry about this separation.

JSON Web Token (JWT)

One of the problems in using a standalone server such as Centrifugo is that it does not know anything about your users and their authentication method, which session mechanism your backend uses. And you need to authenticate connections in some way.

To do this, the first version of the Centrifuge used the SHA-256 HMAC signature when connected, based on a secret key known only to the backend and the Centrifuge. This ensured that the User ID transmitted by the client really belongs to him.

Perhaps the correct transfer of connection parameters and generation of tokens were one of the main difficulties in integrating Centrifugo into the project.

When the centrifuge appeared, the JWT standard was not yet so popular. Now, several years later, there are libraries for generating JWT for most popular languages . The basic idea of JWT is exactly what the Centrifuge needs: confirmation of the authenticity of the transmitted data. In the second version of HMAC, the manual-generated signature was replaced by the use of JWT. This made it possible to remove the need to support helper functions for the correct generation of a token in libraries for different languages.

For example, in Python, the token to connect to Centrifugo can be generated as follows:

import jwt import time token = jwt.encode({"user": "42", "exp": int(time.time()) + 10*60}, "secret").decode() print(token)

It is important to note that in the case of using the Centrifuge library, you can authenticate the user in a way that is native to Go — inside the middleware. Examples are in the repository.

GRPC

During the development process, I tried GRPC bidirectional streaming as a transport for communication between the client and the server (in addition to Websocket and HTTP-based SockJS foldbacks). What can I say? He worked. However, I have not found a single scenario where the bidirectional GRPC streaming would be better than Websocket. I looked mainly at the server metrics: at the generated traffic through the network interface, at the CPU consumption of the server in the presence of a large number of incoming connections, at the memory consumption per connection.

GRPC ceded Websocket in all respects:

- GRPC generates 20% more traffic in similar scenarios.

- GRPC consumes 2-3 times more CPU (depending on connection configuration - all are subscribed to different channels or all are subscribed to one channel),

- GRPC consumes 4 times more RAM per connection. For example, on 10k connections, the Websocket server has 500Mb of memory, and GRPC - 2Gb.

The results were enough ... expected. In general, I didn’t see much sense in GRPC as a client transport - and deleted the code with a clear conscience until perhaps better times.

However, GRPC is good at what it was primarily created for - to generate code that allows you to make RPC calls between services according to a predetermined pattern. Therefore, in addition to the HTTP API in Centrifuge, there will now be support for the GRPC-based API, for example, for publishing new messages to the channel and other available server API methods.

Customer problems

By the changes made in the second version, I removed the mandatory library support for the server API - it became easier to integrate on the server side, however, the client protocol in the project is different, has changed and has a sufficient number of features. This makes the implementation of clients quite difficult. For the second version, we now have a client for Javascript , which works in browsers, should work with NodeJS and React-Native. There is a client on Go and built on its basis and on the basis of the gomobile project of bindings for iOS and Android .

For complete happiness, there are not enough native libraries for iOS and Android. For the first version of Centrifugo, they were locked out by the guys from the open-source community. I want to believe, something like this will happen now.

Recently, I tried my luck by sending an application for a MOSS grant from Mozilla , intending to invest money in the development of clients, but was refused. The reason is not enough active community on Github. Unfortunately, this is true, but, as you can see, I take some steps to improve the situation.

Conclusion

I have not voiced all the features that will appear in Centrifugo v2 - a little more information is in the issue on Github . The server release has not taken place yet, but it will happen soon. There are still unfinished moments, including the need to add documentation. Prototype documentation can be viewed at the link . If you are a Centrifugo user, now is the right time to affect the second version of the server. A time when it’s not so scary to break something in order to do better later. For those interested: development is concentrated in branch c2 .

I find it difficult to judge how much the Centrifuge library, which lies at the heart of Centrifugo v2, will be in demand. At the moment I am pleased that I was able to bring it to the current state. The most important indicator for me now is the answer to the question “would I have used this library myself in a personal project?”. My answer is yes. At work? Yes. Therefore, I believe that other developers will appreciate.

PS I would like to thank the guys who helped with business and advice - Dmitry Korolkov, Artemy Ryabinkov, Oleg Kuzmin. Without you it would be tight.