Unpacking Macintosh Original Bitmap Fonts

I'm a big fan of the

Chicago raster headset from Susan Kare. If you are older than 25, then it is familiar to you as the Macintosh system font from the 1980s to the 1990s, and then it was called an encore for the small screens of the first iPods. Behind the fame of the headset is a solid job. Small raster letters make it difficult to impart a unique and harmonious personality, but

Chicago does it: a high-contrast chopped-up font with a handful of key curls that create a friendly impression. Looks like that:

I love his controls u, v, w, m, n. Recently, I prepared a very useful

course on the design of modern fonts , after which I wanted to make out

Chicago and see if you can learn more about how this design works. This font is not on the current MacBook. I searched online, but quickly realized that in all collections of free fonts there are only fakes.

Since the font is not only its pixels, but also its intervals, I wanted to see the original source material for

Chicago . To do this, it took some archaeological digital investigation: the original Macintosh from 1984 was the first mass computer with proportional typography on the screen, and it had a completely unique way of storing and managing fonts. (Standards like TrueType have not yet appeared).

I have some experience in font programming, so I managed to extract genuine 1984 font data with my 2018 computer (technical details are slightly beyond the scope of this article, but if you're interested, they are at the end of the text in a note). After getting the font, raster, and spacing data for

Chicago , I used the same small program to extract all the other bitmap Macintosh fonts.

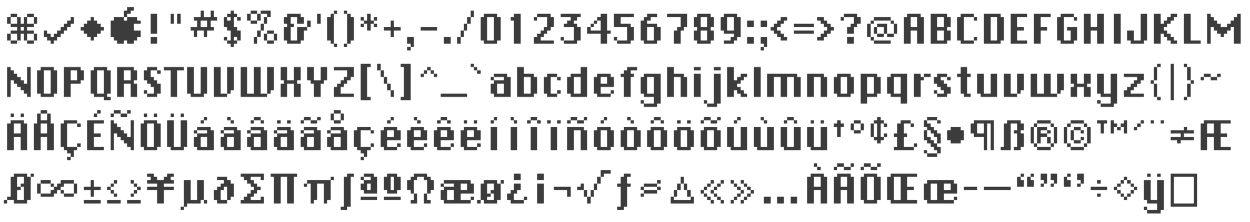

Here is the complete

Chicago table in its only 12pt native size:

Capital M really does it

Capital M really does itThe character spacing above is displayed as intended. It works well, but if you look closely, in some places it is not perfect. For example, capital H and I are too far apart. Like i and j in lowercase. If you were developing this font today, you would want to adjust the

kerning (spacing) of these particular pairs when they appear next to each other.

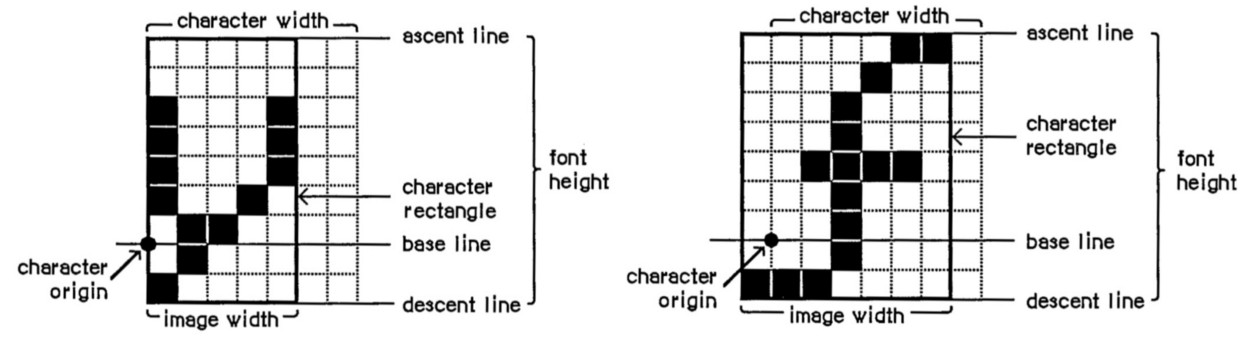

But Mac bitmap fonts did not support modern kerning for individual pairs. Instead, each character of the bitmap image was accompanied by a fixed amount of space left and right, as well as instructions on where to start drawing the character relative to the location of the “pen”.

Here is a visual explanation of the specification and drawing of characters, taken from Apple's

Inside Macintosh documentation:

Source: Inside Macintosh, Volume I (1985)

Source: Inside Macintosh, Volume I (1985)There was some variety in the intervals, but it was required to fix it in each symbol. This was complicated by the fact that raster fonts necessarily coincide with pixels on the screen: you cannot have a fractional interval, therefore, by definition, perfect positioning is impossible.

What we see is forced conservatism with kerning: let us look more or less normal all the time than truly bad in some cases. In

Chicago , the spacing between characters is usually two pixels. There are a few cautious exceptions: take a close look, for example, on the capital T and the lower case r.

Here is a small example that shows both the strengths and weaknesses of the

Chicago intervals:

It would be interesting to recreate

Chicago with identical bitmap images, but add pairwise kerning. So you can improve the font, although it will lose some of its unique identity. Here is my version of the same text with several manual spacing settings:

(I want to see a half-pixel interval here to death)

(I want to see a half-pixel interval here to death)

There are several other original Macintosh raster fonts, almost all are designed by Caret and

named after world cities .

Geneva is a low-contrast chopped-up font (supposedly a clever reference to

Helvetica , but this is definitely not a fake).

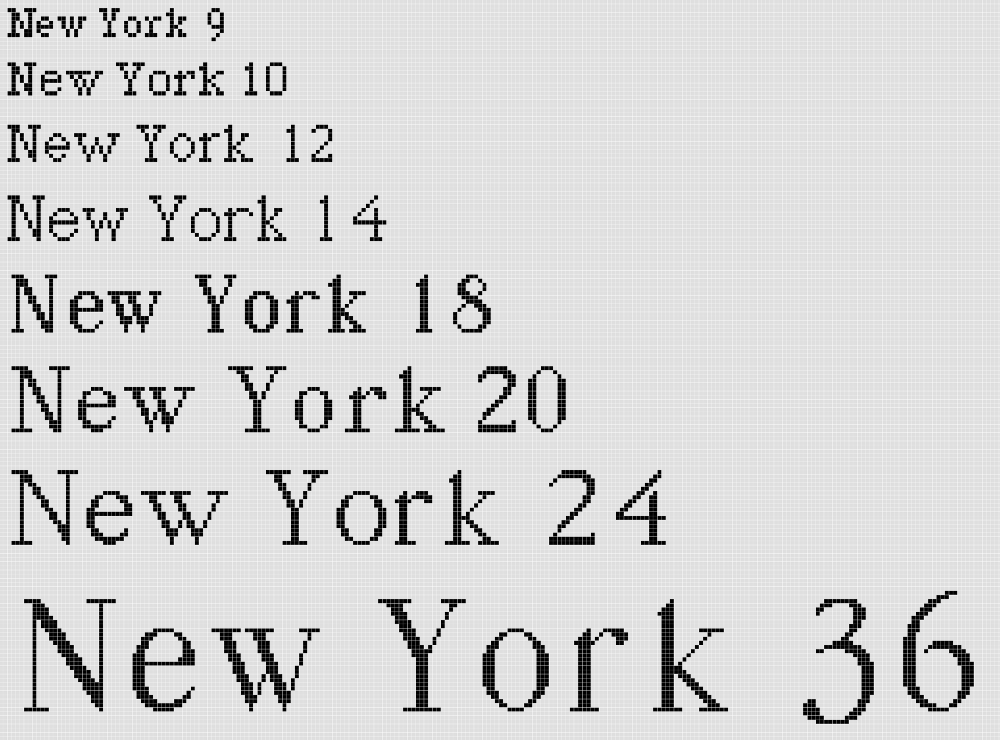

New York is a strict serif text available in several sizes.

New York exemplifies the creativity and coarse design of a raster font. It has many details (contrast) on large sizes, which suddenly disappear below 18 points:

Why does the lower case w lose its overlap on sizes 12 and 14, recovering only 10?

Why does the lower case w lose its overlap on sizes 12 and 14, recovering only 10?(Hmm, this

is something like ).

San Francisco is the name of the

current Apple

standard font for corporate branding, as well as the user interface on all platforms. But long-time Mac users can remember the original ransom-style font with the following title:

Long-time residents of San Francisco may also see some kind of metaphor in the same typeface, but this is a completely different story.

Long-time residents of San Francisco may also see some kind of metaphor in the same typeface, but this is a completely different story.

In any case, what is there for the hidden sheep, you ask? Well, the deconstruction of the original Mac font resources revealed something mysterious: in several fonts, although not in all, there is an unexpected secret character hidden next to the regular ones.

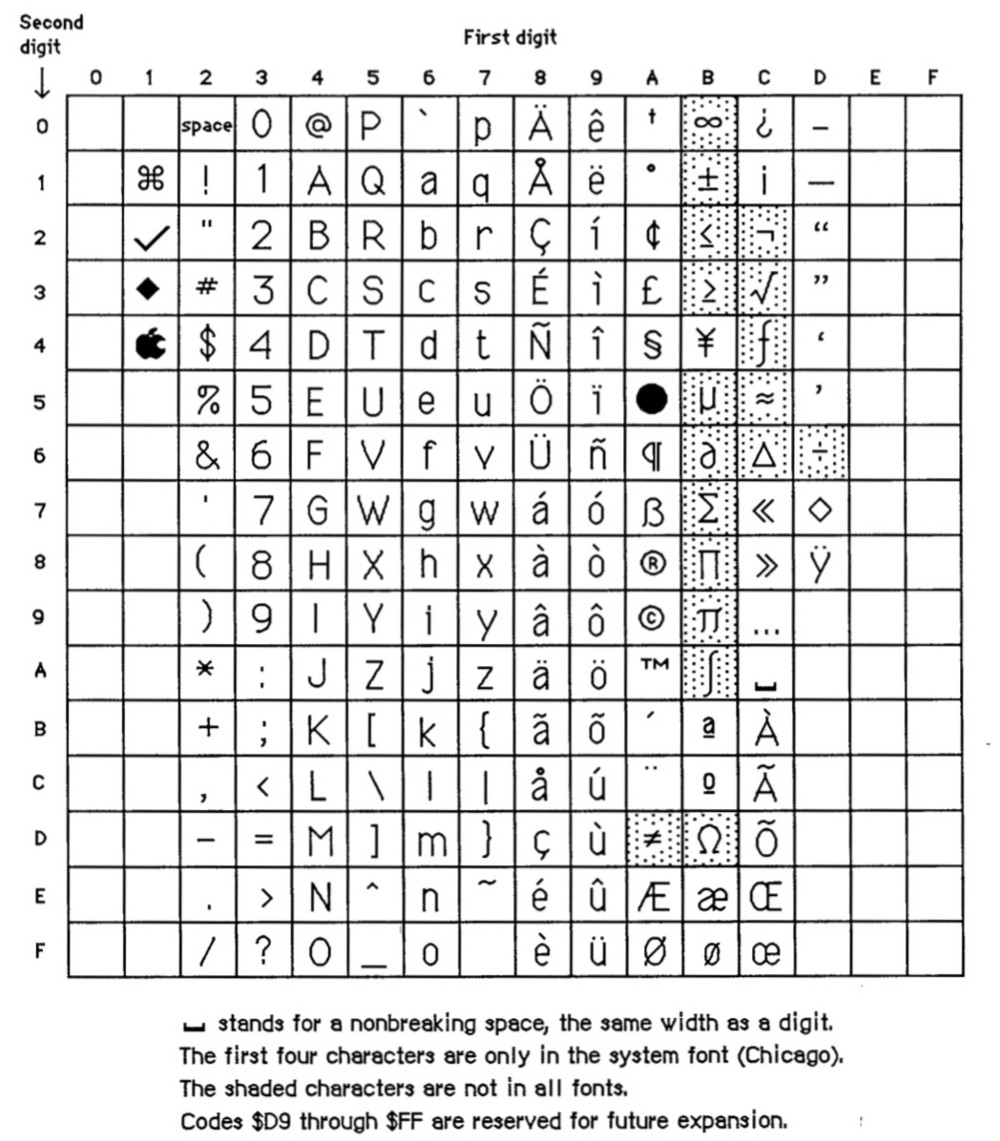

The fact is that back in the 1980s, no more than 256 characters were available. Different platforms assigned codes to characters in slightly different ways. The original Macintosh used a system that would eventually be called Mac Roman. In 1984, she had no name yet, but she looked like this:

Source: Inside Macintosh, Volume I (1985)

Source: Inside Macintosh, Volume I (1985)If you read the table from top to bottom from left to right, you can see that it looks like the full set of

Chicago characters given above. In other words, Chicago has a font character for each of the occupied fields on the chart.

But there are two empty areas in the table: the left side with low code numbers is reserved for non-printing control characters by agreement, and the right side, which is described in the documentation as follows:

"Codes from $ D9 to $ FF are reserved for future expansion .

"So these upper values (from the

hexadecimal value of $ D9 to the last $ FF) do not correspond to any keys on the keyboard and no combinations for international or other characters. So there is no reason for any bitmap information to exist in any font for an inaccessible character code ... right?

ZheneeeeThe Geneva version on 18 points

ZheneeeeThe Geneva version on 18 points includes all the familiar characters, but in the $ D9 position here is a charming sheep shown above. On other sizes,

Geneva has different little icons in this place (rabbit, hieroglyph, Mac icon). If you go down by 9 points, then the sheep comes back again, but already tiny!

Tiny sheep on 9 points

Tiny sheep on 9 pointsIn

Chicago, there is no character in the $ D9 position. However, in

New York it is, different for each font size. Some images are repetitions of icons from non-alphabet fonts (

Cairo and

Taliesin ). But others, like a sheep and like cute paw prints (below) from

Athens , are not there - these are fancy Easter eggs.

If you know what to look for,

here are developer tools that can show you hidden images. But I don’t think that there is any way to see or use these $ D9 characters in a classic Mac OS in a normal way.

The full character sets of many of the original Macintosh fonts are

downloaded here if you want to look at all the Easter eggs (or study the design of the pixel grid in a convenient format).

In classical Mac OS there was very little constant and operative memory, as well as computing power. Susan Kara, Bill Atkinson and others have done a lot in terms of design and technology, having so few resources, and even left us these hidden doodles that digital archaeologists stumbled upon after so many years.

Note: Methodology . I used the Mac emulator on a modern MacBook Pro to boot System 7. There I mounted the System 1 and 2 images and copied their system files and font files to the HFS + volume on the host to save resources (and font data). The rezycle user-friendly application helped to break resource data into binary files. The FONT binary resource format is documented in Inside Macintosh in the section on Font Manager. Also describes the basic algorithm for rendering text QuickDraw. That was enough to write a small program for parsing font data and rendering text — with an extra pixel grid to better show character design and spacing. I used this program to create all the samples published earlier in this article.

I uploaded the cleaned program code to github . There's also a folder filled with rendered characters.