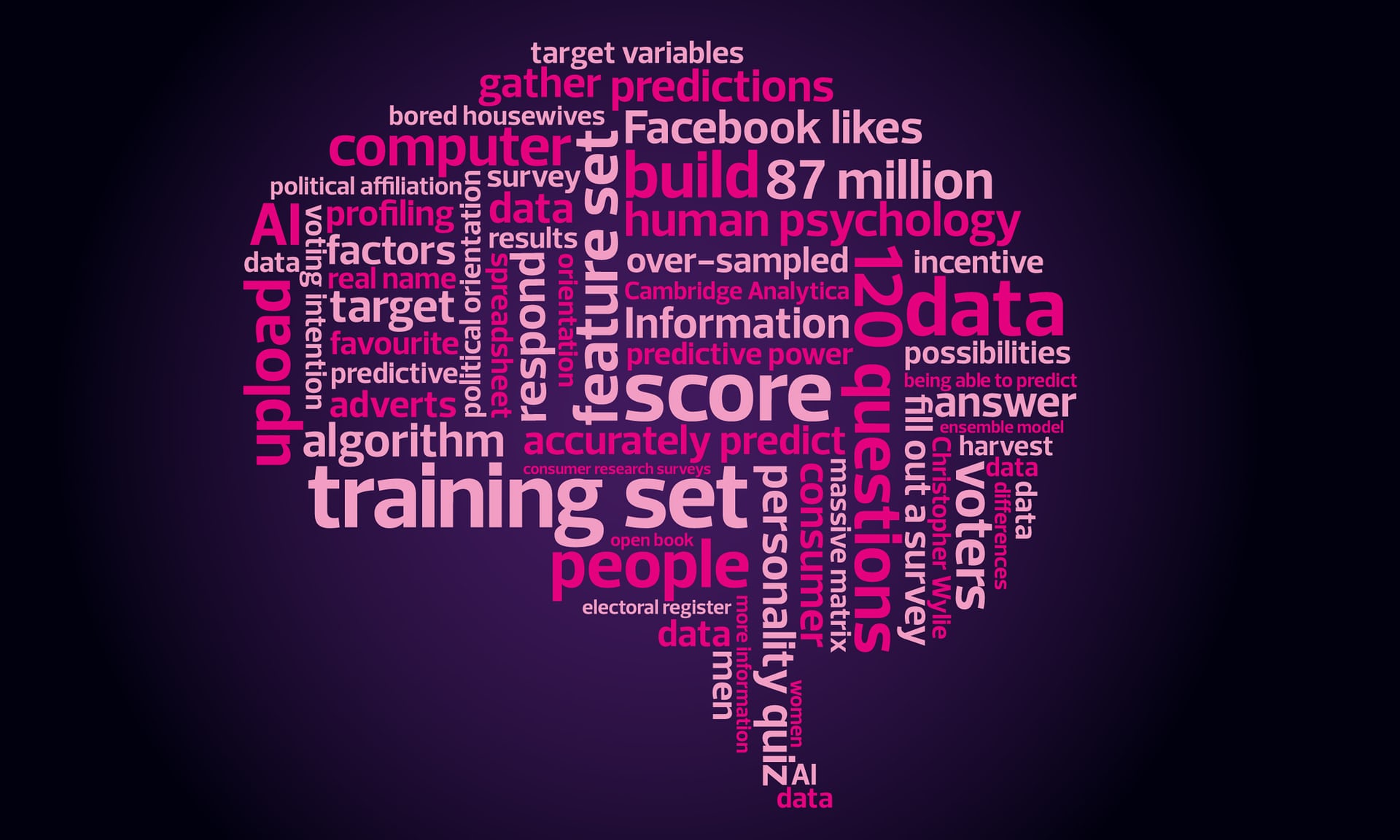

Informant Christopher Wiley explains the science behind Cambridge Analytica’s mission of turning polls and data from Facebook into a political weapon.

How did the 87 million entries collected from Facebook become an advertising campaign that can change the outcome of an election? What does the procedure for collecting this amount of data? What does this data tell us about ourselves?

The scandal with Cambridge Analytica has raised many questions, but for many the unique selling proposition of the company, which last week announced its closure, remains a mystery.

Especially for those 87 million people who are interested in what exactly happened to their data, I went for clarification to Christopher Wiley, a former employee of the company, who told everyone in the Observer edition about her problematic actions. According to Wiley, for this kind of work, quite a bit of information about data processing science, bored rich women, and human psychology is needed.

The first step, he explained on the phone, trying to catch a train: "When creating an algorithm, you first need to collect a test data set." That is, it does not matter how sophisticated technologies will be used to collect data - first you have to collect them in the good old way. Before you start using likes on Facebook to predict a person’s psychological profile, you need to get several hundred thousand people to pass a psychological survey of 120 questions.

Test data will be all the data at once: Facebook likes, psychological tests, and everything else, on the basis of what you want to learn. Most importantly, it should contain a "set of attributes": "The basic data on the basis of which you want to make predictions," says Wiley. “In our case, this is Facebook data, but it may be natural language texts or data on clicks,” is the complete record of your online activity. “These are all data that can be used for predictions.”

On the other hand, you will need your “target variables,” as Wiley says, “what you are trying to predict. In this case, personal characteristics, political orientation, and so on. "

If you use one thing to predict something else, then a simultaneous review of these two things can help you. “If you need to know the relationship between Facebook likes in your feature set and personal qualities as target variables, you need to see them at the same time,” says Wiley.

The Facebook data underlying the history of

Cambridge Analytica is a fairly abundant resource in terms of data processing science - and even more so it was such in 2014, when Wiley first began working in this area. Collecting personal qualities is much more difficult: despite the conclusions that can be drawn from the popularity of

BuzzFeed questionnaires, it is quite difficult to get a person to complete a test for 120 questions (this is the length of a short version of one of the standard psychological surveys,

IPIP-NEO ).

But “quite difficult” is a relative concept. “For some people, the motivation to take the survey was financial. If you are a student or are looking for a job, or just want to earn $ 5, then this is the motivation. " In reality, according to the poll, according to Wiley, they distributed between $ 2 and $ 4. Increased cost relied on for “groups that are harder to reach.” The smallest chance of passing the survey, and therefore, the greatest reward was due to black Americans. “Other people go to the polls because they are interested, or out of boredom. Therefore, we had a bust of data on wealthy white women. If you live in the Hamptons [elite housing area on

Long Island / approx. transl.] and you have nothing to do during the day, you fill out surveys of consumer studies. "

Personality questionnaires use 120 questions to build a personality profile along five different axes - a model of “five factors”, which is called “OCEAN” in the jargon - an abbreviation of “openness to new experience, consciousness, extraversion, desire to like and neuroticism” [openness to experience , conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, neuroticism].

The model divides personal qualities into groups that, apparently, persist in different cultures and at different times. So, for example, those people who describe themselves as “loud” will most likely describe themselves as “outgoing”. If they agree with such a description today, they will agree with him a year later. These groups are more likely to appear in any language. And if one person reacts to something negatively, then he will have obvious and noticeable differences from people who react positively.

These properties of the model make it useful for building a profile of people, says Wiley - unlike other popular psychological profiles, such as the

Myers-Briggs typology . In the testing phase, Facebook was virtually unaffected. Surveys were offered on commercial data research sites - first on the Amazon Mechanical Turk platform, then through the Qualtrics operator (the operator, according to Wiley, was changed because Amazon has a problem with users who are very keen to fill out the questionnaires - as a result, the results of the polls are distorted ).

“Not just the right - responsibility / protect the second amendment ”

“Not just the right - responsibility / protect the second amendment ”

Advertising an election campaign that was tested for performance in Cambridge AnalyticaFacebook connected only at the very end. To get paid for filling out the questionnaire, users had to log in on the website and allow access to the data for the survey application created by Alexander Kogan, a scientist from the University of Cambridge. His research on personal profile building using Facebook likes gave Cambridge Analytica, sponsored by

Robert Mercer , the perfect chance to quickly enter the market. Kogan claims that Cambridge Analytica assured him of the proper use of the data, and said that he was used "as a scapegoat for both Facebook and Cambridge Analytica".

For the user whose data was collected, the process was quick: “Click on the application, get the money code”. But in these few seconds a lot of important things happened. First, the application collected all possible user data. The psychological profile is the target variables, and the data from Facebook is the “feature set”: the information collected by the data processing specialist of all users, which he will use to accurately predict the features he is interested in.

Also, the application collected personalized information like the real name, location, contacts — something that could not be found on sites with surveys. "This means that the information could be compared with a real person, and his - with the register of voters."

Secondly, the application did the same for all friends of the user who installed it. And suddenly, hundreds of thousands of people to whom you paid a couple of dollars to fill out a questionnaire, and whose identity is a mystery, turned into millions of people whose Facebook profiles are an open book.

It is at this moment that the last transformation takes place. How to turn hundreds of thousands of personal profiles into several millions? Leveraging large computer power and a massive table of opportunities. “Although your sample includes 300,000 people, your characteristic set is already 100 million,” says Wiley. Every Like on Facebook from a dataset becomes a separate column in this huge matrix. "Even if one entry occurs for the entire set, it will already be a feature."

“Then all the data is gathered into a complex model,” says Wiley. - At this point, you use different families, or approaches to machine learning, since each of them has its strengths and weaknesses. And then they sort of vote, and you mix the results and produce a conclusion. ” At this point, the science of data processing becomes art: the exact set of input data in each of the approaches is not carved into granite, and there is no one, “correct” way to collect it. In the academic world, this is sometimes referred to as “graduate student training” - the moment after which it remains to do what to move on through trial and error. And yet it worked quite well, and as a result, according to Wiley, "we created 253 algorithms, that is, there were 253 predictions for each profile record." The goal was achieved: a model that could, in fact, take likes from Facebook and, working in the opposite direction, fill all the columns in the table, guessing about the personal qualities of a person, his political predilections, etc.

By the end of August 2014, Wiley had his first successful results: 2.1 million recreated profile records for 11 targeted US states. The plan was to use the data to create and improve advertising messages in the Republican campaign sponsored by Mercer and

Stephen Bannon , and reach the 2016

primaries (Wiley left the company before them). "This number means not only all the people for whom we collected data from Facebook, data on polls and consumer data, but also built on 253 predictions added to them in the profile."

These 253 predictions were the “secret ingredient” that Cambridge Analytica presented as a unique proposition to consumers. Using data from Facebook alone, advertisers are confronted with too wide demographic samples, and several narrower categories, defined algorithmically - whether you like, say, jazz, or your favorite football team. But with 253 predictions, Cambridge Analytica could, according to Wiley, adjust advertising like no other: a neurotic easily agreeing extrovert voting for democrats would be completely unresponsive to such advertising as an emotionally stable intellectual introvert, even if the same messages, if they were interchanged, would have the opposite effect.

Wiley mentions such a calming political statement by the candidate as a desire to increase the number of jobs. “Jobs in the economy is a good example of a meaningless statement. In economics, all are behind the availability of vacancies. Therefore, the use of a simple statement, “I stand for vacancies in the economy,” or “I have a plan to correct the situation with vacancies in the economy,” does not allow you to differ from your opponent. ”

“But we found that if we analyze what the notion of vacancies means for each individual person, it turns out that different people have different constructions with different motivations and a set of values.”

In practice, this means that the same chatter can be expressed in different ways for different people, creating the impression of a candidate influencing voters on an emotional level. “If you speak with a conscious person - with high marks for the C parameter in the OCEAN model [honesty, good faith] - you are talking about the possibilities to achieve success and the responsibility that the workplace carries with it. If this is an open person, you are talking about the possibility of growing as a person. With a neurotic, you rest on the safety that the workplace will give to the family. ”

Due to the network nature of modern campaigns, in theory, all these messages can be simultaneously delivered to different audiences. By the end of the campaign, when the messages have already taken root, they can even be automated using an algorithm that scans the dictionary in search of the perfect combination of words for each of the subgroups.

“See what“ marriage ”means, and come back to me / Because traditions are not outdated”

“See what“ marriage ”means, and come back to me / Because traditions are not outdated”

Advertising an election campaign that was tested for performance in Cambridge AnalyticaOf course, this is not 100% chatter. One message was used by right-wing attackers of same-sex marriage. “It's funny that the message turned out to be so insulting and homophobic, despite the fact that it was created by a team of homosexuals,” says Wiley. - It was aimed at conscious people. There was a picture of the dictionary and the inscription “See what“ marriage ”means, and come back to me." For a conscious person, the message looks convincing: the dictionary is the source of order, and such a person respects the structuredness. "

At some point,

psychometric targeting goes into the

politics area

of the dog whistle . For example, wall images have proven effective in immigration campaigns. “Conscious people love structuredness, so from their point of view, the solution to the problem of immigration should be orderly, as illustrated by the wall. You can create a message that for some people does not make sense, but for others it is filled with meaning. When demonstrating this image, some people will not understand that we are talking about immigration, while others immediately recognize it. ” From the point of view of Wiley, the real problem was a political “sandwich with nothing” waiting for something to be put on it. "No one likes a sandwich without anything." He says that the data should “figure out a particular taste or flavor” that will make the sandwich attractive.

And while it certainly was a very complex targeting machine, questions remain about the Cambridge Analytica psychometric model - which Wylie will probably not answer better. When Kogan provided evidence to Parliament in April, he argued that the result was hardly better than just a random assignment of OCEAN ratings. Perhaps, of course, this small difference is enough, or, perhaps, Cambridge Analytica just traded in another

snake oil . And even if individuals were correctly marked with these five factors, was it really so simple to find specialized advertising for them, like appealing to the love of order, fear, or something else?

But, considering all this, there is still something in it. Pay attention to the 2012 patent on "determining the personal characteristics of the user based on the exchange of messages in social networks." “The storage of personality characteristics can be used as target criteria for an advertisement, to increase the likelihood of positive user interaction with the advertisement,” as indicated in the patent The author of the patent is the Facebook company itself.