In the world is another tension. Heads of state showered each other with formidable “official bodies” and frantically groped for nuclear bob. Like, is it here, next. Mankind has become accustomed to such situations, especially since with the development of mass communications and the emergence of nuclear weapons, the feeling of periodic tension grew into a permanent one. Even the masses of cultural works are devoted to the consequences of a nuclear apocalypse.

Under the cut an interesting story about how American techies and the military built an advanced nuclear threat warning system, which became the prototype of the modern world wide web.

In the courtyard stood May 1959. Nuclear weapons were still a wonder, but the brave Americans managed to break them in Herosim and Nagasaki, so the consequences of a nuclear strike to all of humanity were clear not only in theory. At that time, the Soviet Union was considered the evil empire, and the US authorities considered the possibility of a nuclear strike by the Soviets to be quite realistic. It had to be ready for it, which required the creation of a well-coordinated and operational alert system that could instantly warn of a nuclear strike.

For development, the US government turned to the largest telegraph company Western Union. The system was required to monitor the hundred targeted areas of the country, and continuously report their status to the command posts of the US military. Almost a year later, in March 1060, Western Union developed and put into operation the first prototype.

Initially, the system monitored a halt in the fourteen target areas of the eastern states. It consisted of 37 detectors and generating stations, one main control center, and the display center at the Pentagon. At the beginning of 1962 the system was brought to the national level and it began to work for the benefit of the American people. This alert system is known as the Western Union Bomb Alarm-Display System 210-A.

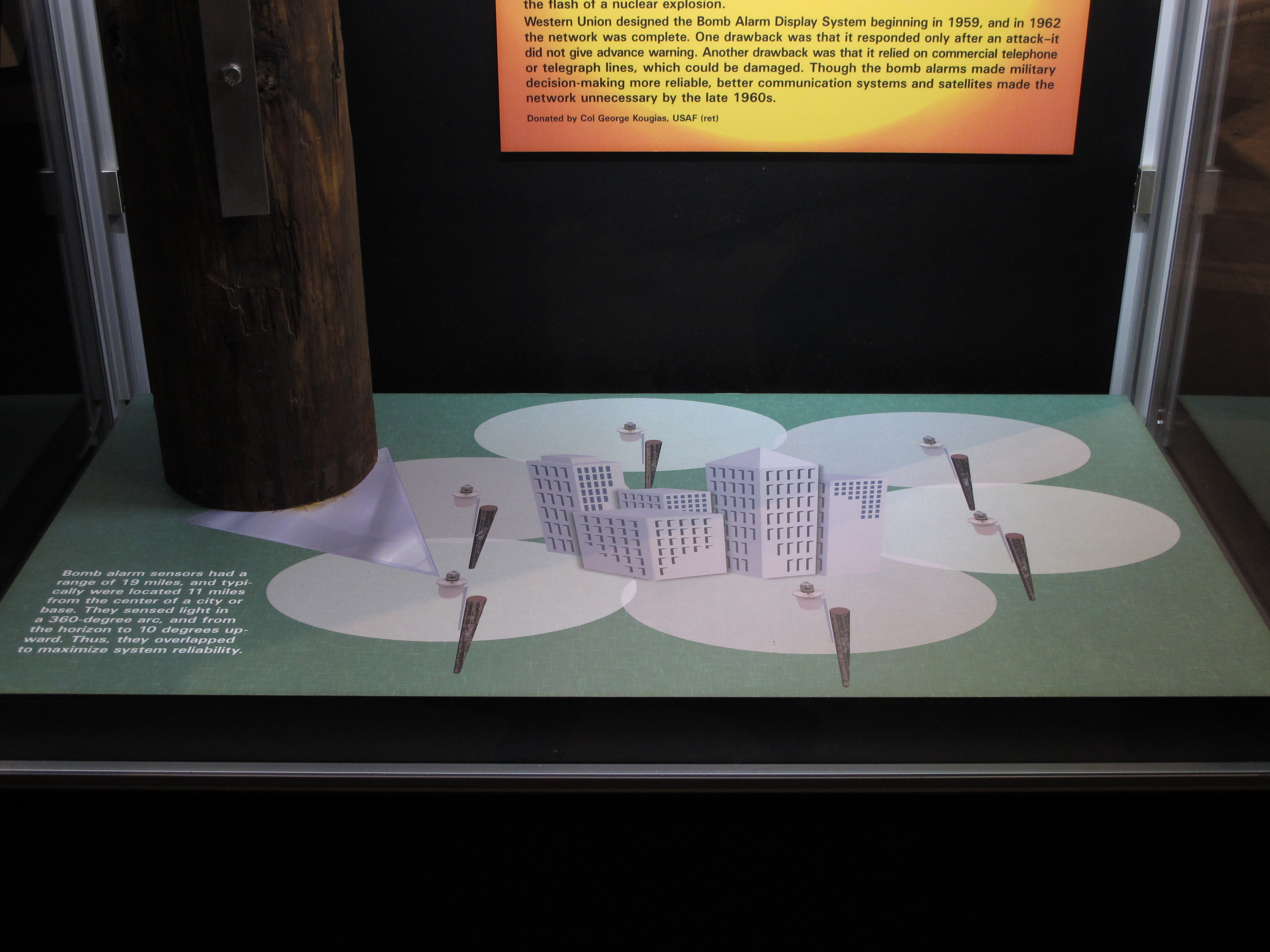

The basis of this complex was a network of telegraph poles, which enmeshed the entire territory of the United States .. At some point, the tops of these pillars began to be decorated with unremarkable cylindrical cans. They were painted white and topped with a Fresnel lens, which allowed beacons to transmit light over long distances.

Installers install cylinders on telegraph poles

Installers install cylinders on telegraph polesAccording to the principle of a nuclear bomb

To understand what constituted a warning system, you need to recall the damaging factors of a nuclear explosion. In an explosion, a nuclear bomb produces three basic types of energy. They are easy to spot. A third of the energy comes out in the form of thermal radiation, consisting of both heat and light. Such radiation instantly causes fires near the epicenter of the explosion. The second type includes the original nuclear radiation, which consists of gamma rays and neutrons. This is about three percent of the total energy. It usually causes severe skin burns. The third type of energy brings the greatest damage after the explosion - this is a blast wave. Its speed is a few seconds less than the speed of thermal radiation.

Theoretically, it is possible to take any of these three components as a basis for detection, however, taking into account all the characteristics, Western Union engineers, of course, turned on the detection of thermal radiation. In addition, thermal radiation from a nuclear explosion has a unique waveform that distinguishes it from all natural sources of thermal radiation.

Western Union Alarm was inconspicuous to the eyes of the man in the street due to the fact that the sensors were installed on telegraph poles. The sensors were installed three within a few miles of the observed area.

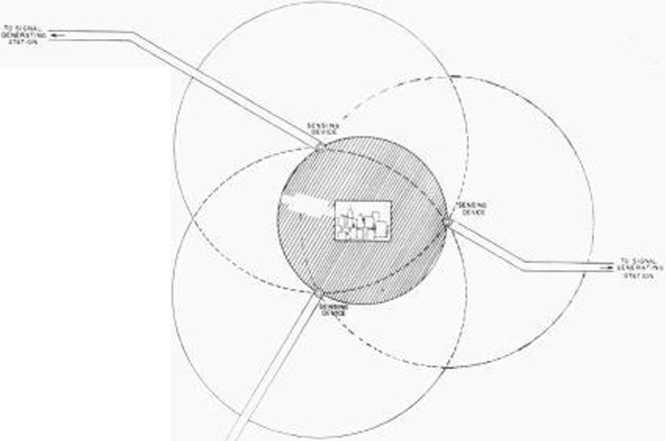

Sensor distribution configuration

Sensor distribution configuration

The sensors were arranged in groups in the form of triangles at a sufficient distance from each other so that in the event of an attack, they had time to report a threat. So, if an explosion occurred at the center of a controlled area at the same time, all groups of sensors should have notified the attack. If one of the sensors came under attack of danger, the other two instantly reported. The signal about the stable operation of the sensors was regularly transmitted via commercial telephone and telegraph lines. The presence of a stable signal indicated that the system did not fix any problems.

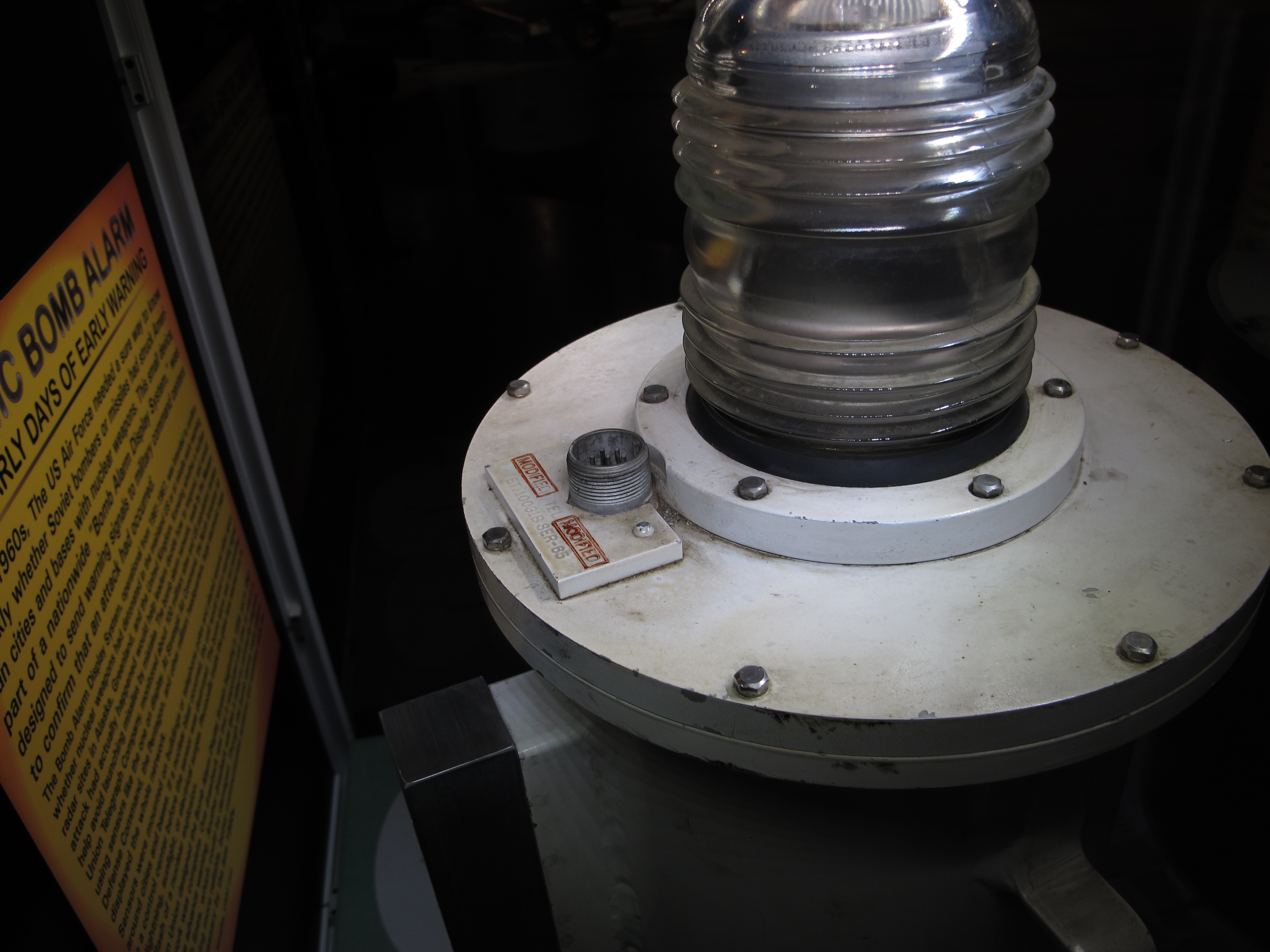

The detector itself was a massive container, inside of which was a cylindrical perforated metal screen, with a light attenuation factor of 100. Inside the screen are photocells installed in the focus of the lens.

The sensor was based on special photovoltaic cells made of silicon. Their task was to react to the light energy from a nuclear flash. The response time of these elements was only a few microseconds. The sensor responded only to a nuclear flash.

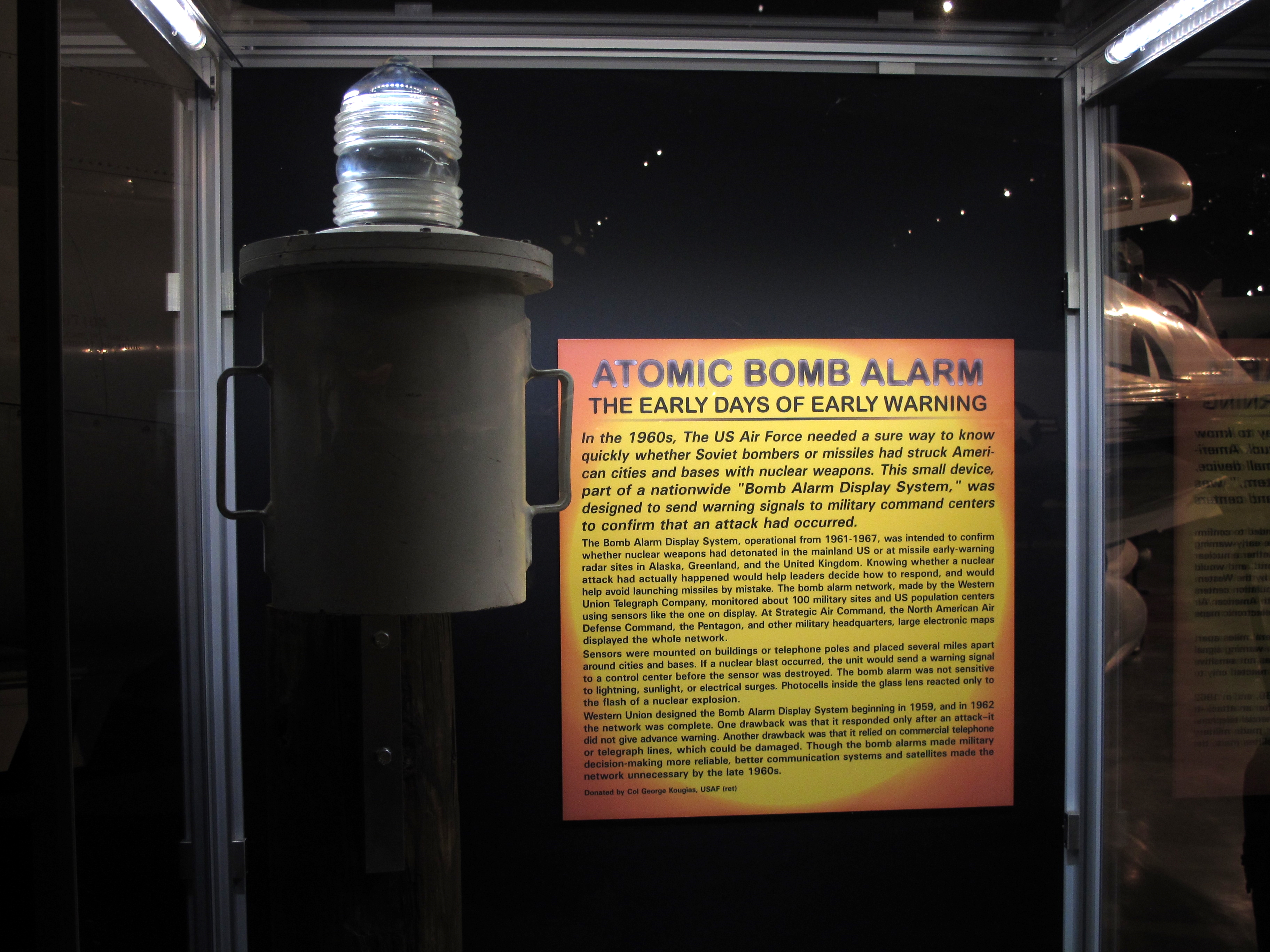

It looks like the "defenders of America in the 60s" who now live in the museum

It looks like the "defenders of America in the 60s" who now live in the museumSignal generation

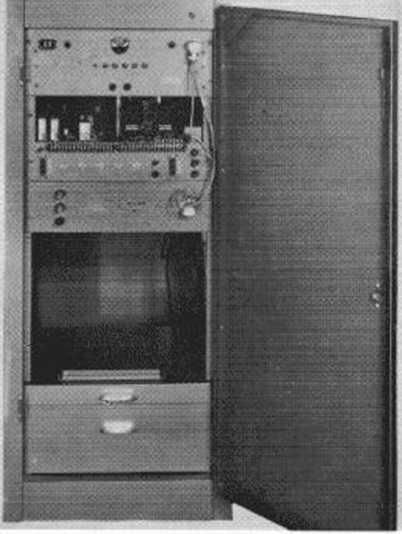

Signal conditioning stations were located, as a rule, thirty kilometers from the transmitters. The signals from the detector came here, and then they were converted into special reports - “green” or “red”. The first said that the detectors did not fix any problems, and the second warned about the fixation of a nuclear outbreak.

View of the signal conditioning station outside

View of the signal conditioning station outside

The stations were connected in series with loops, and together they formed a universal reporting system.

Further, the stations transmitted a signal from each other along the chain. The result was a kind of loop from the stations. Each such loop was under control of the Control Center. Under normal operating conditions, the Control Center periodically sent an interrogation signal to all loops connected to it. It was also transmitted along the chain from station to station. At the same time, a message was evaluated on the detector line. If a “green” signal was emitted from the detector, the signal generating station transmitted its “green” report. If a “green” signal did not come from the detector, which could have happened due to interruptions in the operation of the communication line, then a local report was not made. This told the Control Center about possible system interruptions.

The second station in the chain repeated the interrogation signal and prepared to transmit the signal, as the first station did, but taking into account the response of the first station. This procedure was carried out to the end of the line, where each station relayed all incoming traffic and added its own report. The last station in the cycle sent a message consisting of the original request and reports from all stations to the Control Center.

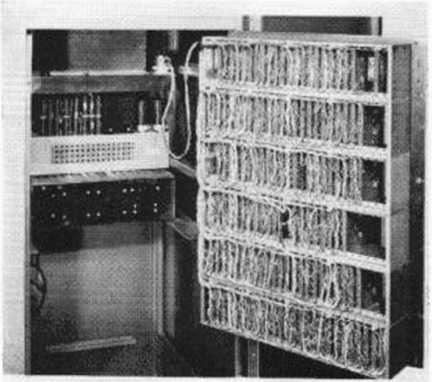

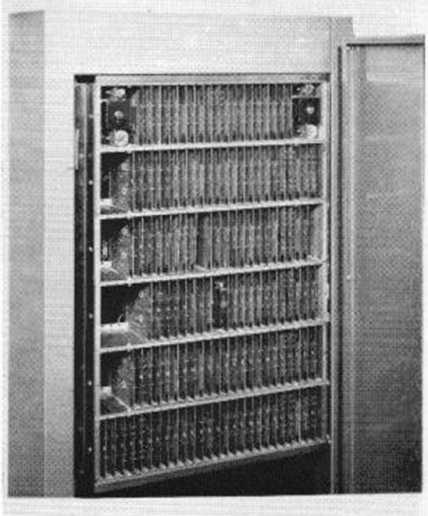

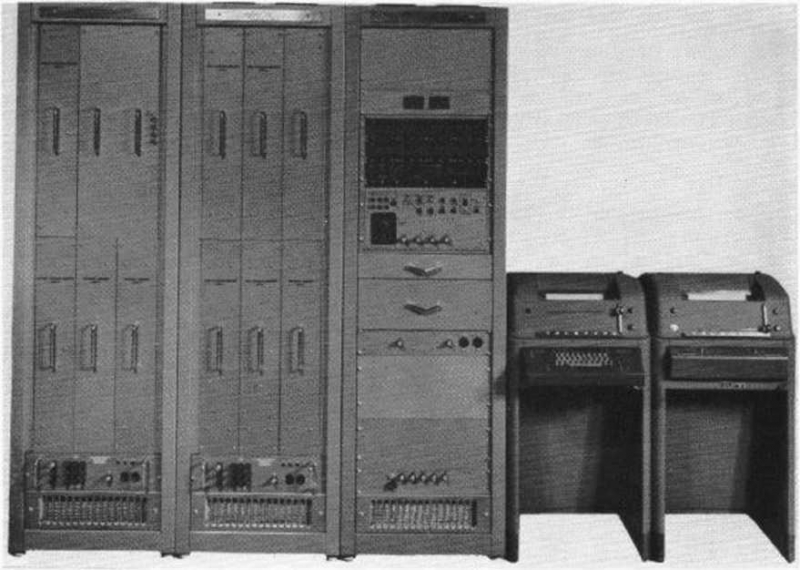

Control center

Control centerIf the signal generating station did not send a survey signal from the Control Center during the interval allotted to it, then it sent its “green” signal automatically. Thanks to this function, the personnel serving the warning system could detect the location of breakdowns in the loops of generating stations. In addition, thanks to this, it became clear which stations were still functioning and were capable of transmitting “red” alarms.

The main control center is the brain of automatic control of the system. All loops of the signal generating station began and ended precisely here. Cyclic polls were initiated from here. All the answers from the signal generation stations also came here.

The control center “knew” the number of signal generating stations that must submit their reports. Upon completion of the survey, "green" reports were transferred to the so-called centers of indication.

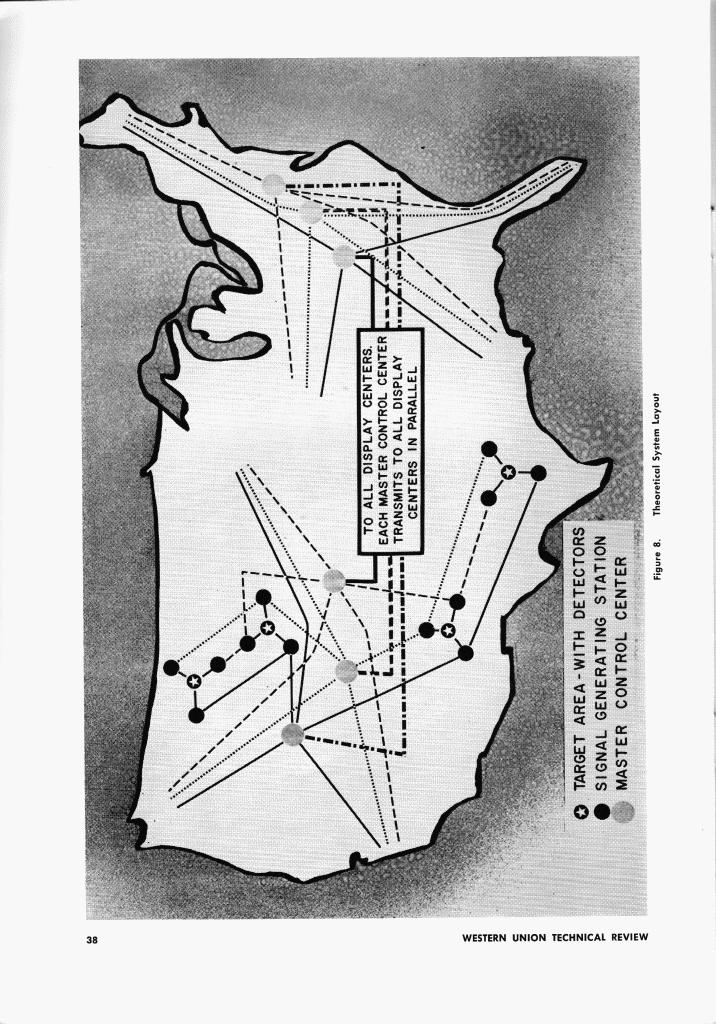

In the common system, which was supposed to cover the whole country, there were six such control centers. They worked in two groups of three, and each group covered about half of the country.

Outline of the nationwide alert system

Outline of the nationwide alert systemEach Control Center transmits all display centers. The system is designed so that each of the three detectors associated with a given target area is tied to a separate main control center through separate objects. This triple diversification improves reliability and continuity of coverage. Each master Control Center polls all connected channels every two minutes.

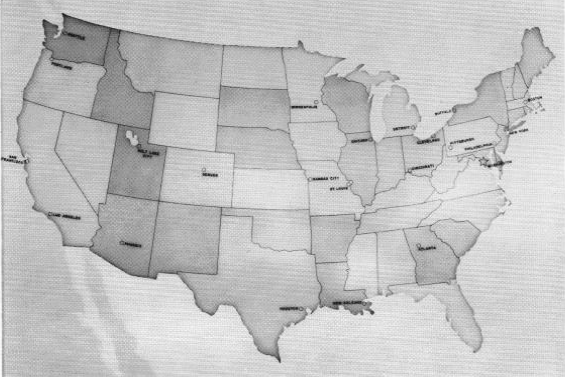

All alerts were sent to the central command posts at the Pentagon, the North American air defense command and the Strategic Air Command. The headquarters of the SAC, in particular, had a giant wall with maps on which they could follow the state of the nuclear confrontation of the Cold War. The Big Board, as it was called, was 80 meters long and two stories high.

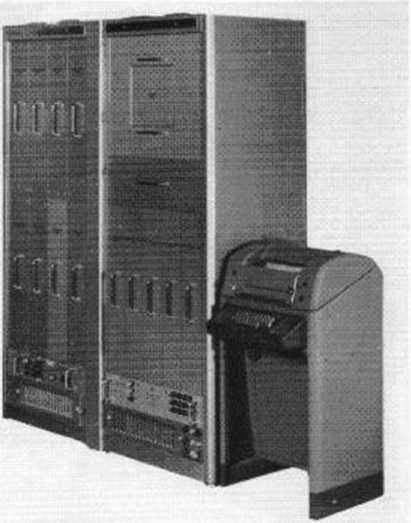

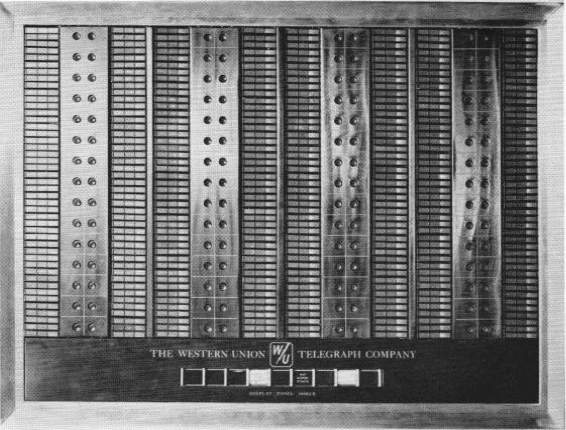

The command centers housed the so-called central displays. Their design was a decoder decoding the signal and outputting it to the printer.

It also included two display panels. One of them was a map with a list of target areas.

On the map, only the “red” report was displayed. Behind the translucent panel, on the front surface of which is a map, in the event of an alarm, a red light came on so that the location of the attack could be determined. The positions of the target areas were visible only in the event of an alarm or its simulation.

On the tabular list, called the communicator panel, three lamps were provided for each detector: red, yellow, and green. One of these lamps burned constantly. Ideally, only the "green" ones were burning, which showed that all equipment and circuits were in working condition. The "yellow" light showed that the equipment or objects associated with a particular detector are faulty and are not able to respond to a sequence of standard signals, but may still be able to respond to an alarm, depending on the type of fault. The “red" light indicates that the alarm. The name of the target area becomes readable only if an alarm is present or simulated second situation for the area. The duty on the panel of your device always knows the status of all detectors.

At the time, it was the most advanced communication system. But she also had flaws. Once, one accidentally damaged detector convinced the military that a country had been subjected to a nuclear strike, and this almost led to sad consequences. In addition, in a real attack, the infrastructure that was supposed to send these types of warnings could have been destroyed by strategic strikes against key network nodes. Seeking to solve these problems, the military began to lay the foundation for a modern communication infrastructure. By the end of the 1960s, the bomb alarm system was considered obsolete. She was replaced by satellite monitoring.

Concerns about the reliability of military communications in a nuclear attack inspired RAND researcher Paul Baran to suggest a network of distributed communication — an idea that has become a revolutionary ARPANET network that has become the forerunner of the modern Internet.