No more American uniforms than jeans with a t-shirt. But after the recent closure of the last factory for the production of

selvage-denim in the country, you may have to completely abandon such a thing as "Made in the USA."

On January 19, 2018, Tod Smith last went through the maple floors of the White Oak denim factory in Greensboro, North Carolina. He worked at this factory from September 1980 - he was able to get a job there when he was only 19. His father, who had worked for White Dec Oak, a corporation of

Cone Mills , for three decades, pulled some strings to arrange his son. Over time, Smith moved up the corporate ladder, became one of the factory electricians, and now, three weeks after the last meters of denim were removed from the looms, his job is to help turn off the electrical system of the factory, which is preparing to close forever.

“It was awful, right ghost town,” says Smith. “All the cars are still there, and it feels as if you could still see people at work.”

Most of the workers of two hundred people did not appear there since December 28 - the company extended the work one day after Christmas, so that the workers would be paid money for the day off - the last generous gesture.

For more than 120 years, Cone Mills has produced cotton fabrics, from

cord to

flannel , for hundreds of clothing companies, with the help of dozens of factories. But it was Selvage Denim from the White Oak factory that won Cone Mills a place in American folklore. “White Oak was an organization,” says Michael Meyer, co-founder of clothing brand Taylor Stitch. “It was a place with which people had strong connections, and they made a terrific product there. They have produced such a good product for so long, and never deviated from it. ”

Cone Mills worker examines denim for defects

Cone Mills worker examines denim for defectsAlmost from its opening in 1905, the White Oak factory was a titan of the industry. At its best, more than 2,000 people worked for her, and she gave out more denim than anyone else in the world, making supplies to companies like Levi's and Blue Bell, the predecessor of Wrangler. It was so large that it had its own power station, schools, churches, baseball fields and hostels for workers. Cone Mills became one of a small number of American denim producers who survived the departure of production abroad, a trend that began in the 1980s - when large brands switched to cheaper, faster to manufacture, ragged denim from Asia and Latin America. When White-Oak finally closed, it was the last factory to produce high-quality selvedge denim in the United States. In certain circles, her passing was perceived as if the closure of the last vineyard in Champagne.

“It’s a shame for our country that we’re unable to maintain an open sole Selvage Denim factory,” says Christian McCann, founder of the men's clothing brand, Left Field NYC. “As soon as I heard about the closure of the White Oak factory, I immediately ordered 3,500 yards of their denim - with all the money I had.”

Such a desirable denim from White Oak was, in particular, thanks to the machines of the factory. From the 1940s, it produced fabric using Draper X3 weaving looms, the most advanced machines of its time, but very far from today's mass production machines, whose microprocessors are capable of producing rolls of flawless fabric. The low-tech X3, together with the factories playing the maple floors, created a small vibration that included small imperfections in the fabric — a slight deflection of the yarns and tubercles on the denim. Technically, these were defects, but imperfections began to be regarded as unique properties, and an aesthetic opposition to the extremely uniform denim of mass production from Asia. It was a denim with a personality of its own.

“The character was felt in its threads, color and shade,” says Vivien Rivetti, vice president of design at Wrangler Jeans. “But, in fact, at the fundamental level, it was a difference in quality.”

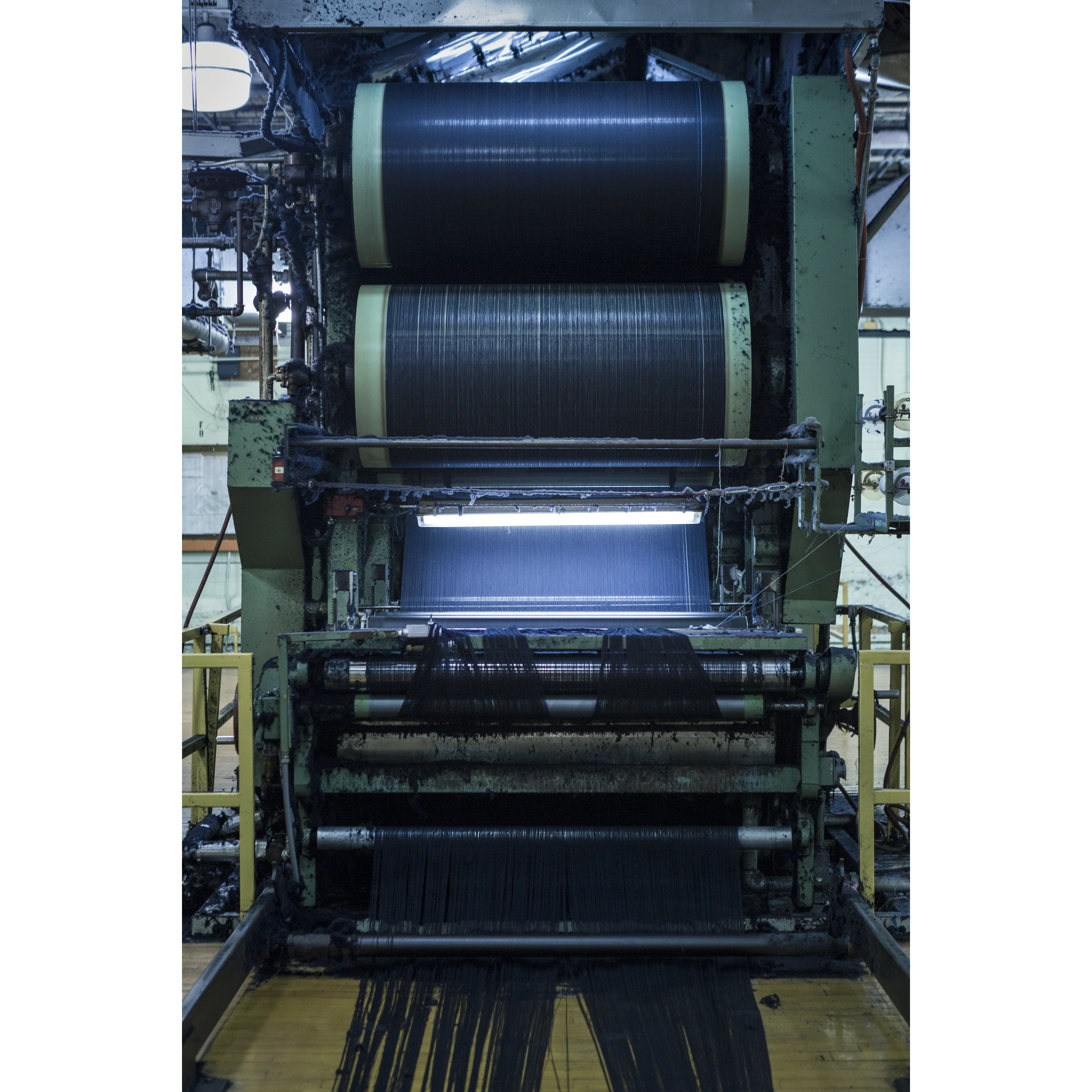

A worker checks the tension on one of the vintage Draper X3 machines.

A worker checks the tension on one of the vintage Draper X3 machines.Selvage does not necessarily mean better quality — it is simply a method of finishing the seam when it is bent into a neat, non-blooming edge inside each leg. But usually selvage denim is denser and thicker, its stitching is stronger, and the indigo color looks better. The Cone Mills factory had all these features. She also had a story and a feeling of nostalgia in the fabric she gave out, so for many fans she became a kind of fetish. “He had such a special, rough, tough look from the 50s,” says McCann.

The White-Oak closure came as a surprise to many, although signs of this have long loomed on the horizon. Selvage Denim, which was once the industry standard, began to die out and fall out of the mainstream in the 1980s, when brands like Wrangler and Levi's switched to a simpler and previously wiped denim. Japanese companies bought American weaving machines for selvage, or made their own according to American drawings, and raw selvedge-denim continued to live as luxury items for men. Cow Mills was one of the few American companies that continued to produce in the 1980s and 1990s.

In 2004, investor Wilbur Ross, now the US Secretary of Commerce, acquired the bankrupt Cone Mills through his company International Textile Group. The time was chosen successfully, because then the trend "buy American" coincided with the boom of men's fashion. The number of workers, which has decreased since the 1980s, has increased, orders have gone. Wrangler, Levi's, Lee and J.Crew began selling premium rulers made from White Oak denim, and small brands like Taylor Stitch, Railcar Fine Goods, Rogue Territory, Raleigh Denim Workshop and Rising Sun began to advertise “100% authentic Denim from Cone Mills White Oak, as American automakers in the 1970s advertised "Corinthian leather" [a

marketing term for leather salons of luxury cars Chrysler / approx. trans. ]. It was a property of elitism and quality that could be advertised.

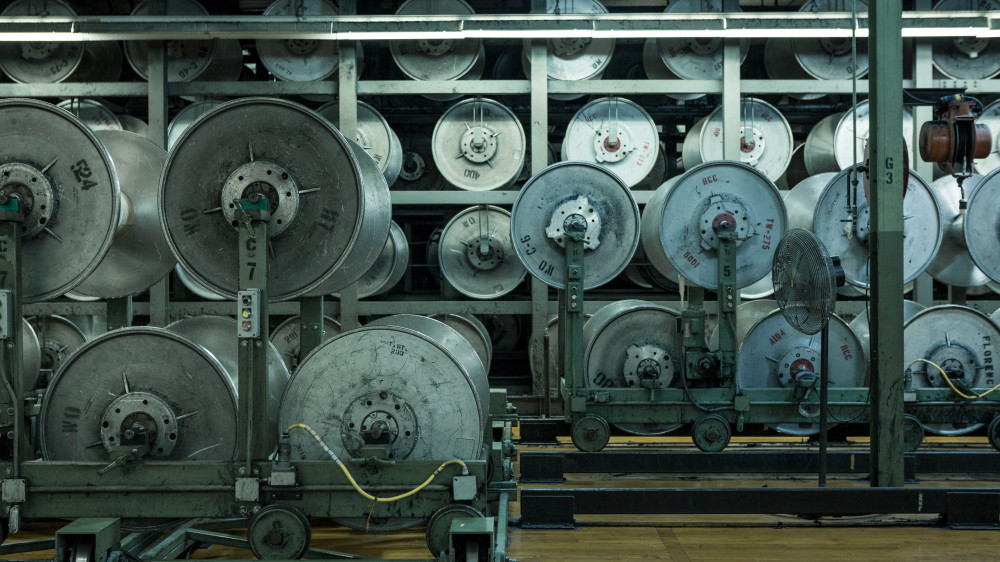

Before each batch of denim was woven on White Oak machines, the dyed thread was covered with a special protective layer in the process called “slashing”

Before each batch of denim was woven on White Oak machines, the dyed thread was covered with a special protective layer in the process called “slashing”“When I first went to the factory, they said to me,“ You can work overtime as long as you want, ”says Ricky Cook, who served 51 X3 machines in the factory,“ because we had so many orders back then. ”

In the late 2000s, the factory moved from a five-day working week to a six- and sometimes seven-day. “We walked quite well then,” says Smith. “Not earning too much, just enough to support it all.” When Ross bought us, he said that while the factory will bring in a little bit of revenue, he will support it. ”

But shortly after Ross was made trade minister at Trump, he sold ITG to investment company Platinum Equity. A year later, ITG announced that it was closing White Oak and dissolving all workers.

White Oak produced almost everything itself, including dyeing and textiles. After its closure, more than 200 people were left without work.

White Oak produced almost everything itself, including dyeing and textiles. After its closure, more than 200 people were left without work.“Honestly, I have foreseen this for many years,” says Smith. - We had such a big factory, and a lot of space was idle just like that. I think it was expensive to support her in her work. We just slowed down and gradually dissolved people. We could do a good job for a year, six months, and then go aground again, and let another 20-30 people go. "

Rivetti and other brand owners were not ready for this. Wrangler even increased her orders in 2017, and she never had any problems delivering denim from White Oak.

Wrangler, Levi's, and all the expensive brands that used White Oak products will easily find Selvedge Denim somewhere else - the Japanese still give out fabrics of the highest quality - but almost certainly the White Oak closure will lead to a fight for its latest products. “When brands start selling the goods they have left in stock, many people will start to panic and switch to collector mode,” says McCann. “People will begin to stockpile.”

51 Draper X3 machines are still on swept maple floors, and there is a dead silence in an untouched building. While no one knows what will happen with the machines, and the company refuses to comment. According to rumors, ITG refused to sell the machines and asked the workers if they would like to come back if the factory opens again. Many of them said yes.

“White Oak was a good place to work,” says Cook, who worked for more than a decade with another Denim producer, Dan River in Virginia. - Most of the people from Greensboro called us "the family of Cone Mills." I've never heard anyone say about the Dan River “Dan River Family”.