There is one underrated paradox of knowledge, which plays a critical role in our advanced hyper-connected liberal democracies: the more information we have, the more we rely on the so-called reputational methods for its evaluation. The paradox is that the incredibly increased access to information and knowledge that we have today does not give us new opportunities and does not make us cognitively autonomous. It only makes us rely even more on the judgments and assessments of other people about the information that has fallen on us.

We are experiencing a fundamental paradigm shift in our relationship with knowledge. From the “information age” we move to the “reputational” one, in which information will have value only if it is already filtered, evaluated and commented on by others. In this sense,

reputation today becomes the central pillar of the public mind. This is the gatekeeper, giving access to knowledge, and the keys to the gate are in others. How the authority of knowledge is built up today makes us depend on the inevitably distorted judgments of other people, most of whom we do not even know.

Let me give you a few examples of this paradox. If you ask why you believe that the climate is undergoing serious changes that can drastically damage future life on Earth, the most reasonable answer you can give is likely to be that you believe in the reputation of information sources to which you usually ask for information about the state of the planet. At best, you trust the reputation of scientific research and believe that an independent assessment of the work is a reasonable way of sifting truths from false hypotheses and complete nonsense related to nature. In a less good case, you can trust newspapers, magazines, television channels that encourage political views that support scientific research in order to give you their final results. And in the second case, you are already two steps away from the sources - you trust people who trust respectable science.

Take an even more controversial truth, on which I wrote a

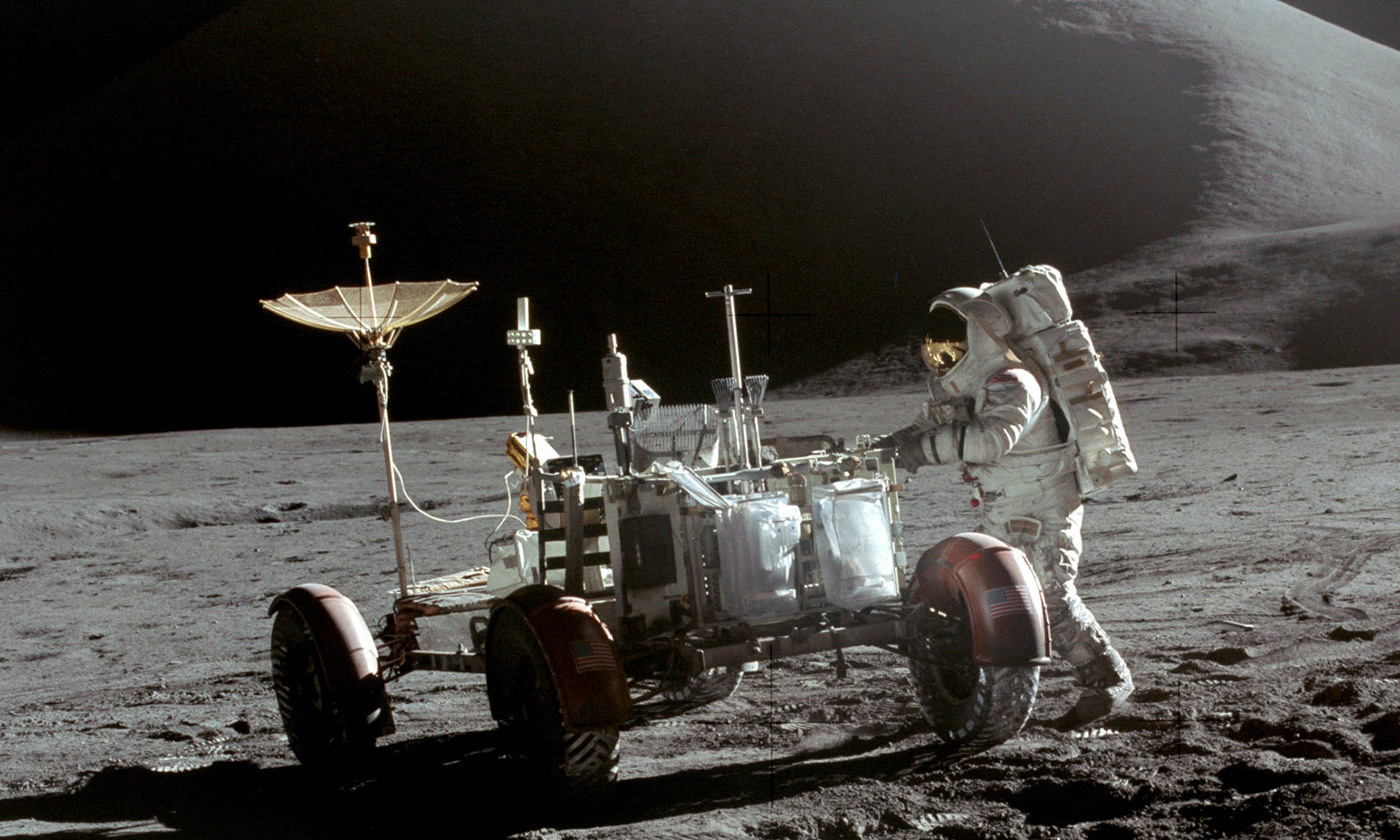

separate work : one of the most notorious conspiracy theories, according to which no one landed on the moon in 1969, and that the whole Apollo program (including six moon landings from 1969 to 1972 years) was fabricated. Launched this theory,

Bill Kaysing , who worked in the print edition of the company Rocketdyne - the one that built the rocket engines for

Saturn-5 . Keysing at his own expense published the book "We have never been on the moon: the $ 30 billion fraud of America" (1976). After its release, a movement of skeptics began to grow, gathering evidence of the alleged fraud.

According to the Flat Land Community, one of the groups still denying the facts, the moon landings were fabricated in Hollywood with the support of Walt Disney and under the direction of Stanley Kubrick. Most of the “evidence” they offer is based on seemingly correct analysis of images from different landings. The angles of fall of the shadows do not match the lighting, the US flag flutters, despite the absence of wind on the moon, the footprints of the steps are too clear and well preserved for soil without moisture. And in general, isn't it suspicious that the program, in which 400,000 people took part, was so suddenly closed? And so on.

Most of the people who can be considered prudent and responsible (including me) will acknowledge such statements, ridiculing the absurdity of the hypothesis (although NASA responded to these accusations

seriously and documentary ). However, if I ask myself on what evidence base I base my belief that there were moon landings, I have to admit that my personal evidence is rather poor and that I haven’t spent a second trying to expose the evidence collected by conspiracy theorists. . What I personally know about these facts consists of a mixture of childhood memories, black-and-white TV news and respect for what my parents told me in later years. Nevertheless, the quality of these testimonies, which was not confirmed by me personally, and the fact that they were obtained from second-hand, does not make me doubt the truth of my opinion on this issue.

My reasons for believing that the moon landing took place go far beyond the evidence related to the event itself, which I could independently collect and verify. In those years, we still believed that such democracy as the American one has a confirmed reputation as honest. But without a value judgment regarding the reliability of a certain source of information, this information from a practical point of view turns out to be useless.

Changing the paradigm from the era of information to the era of reputation must be taken into account when we are trying to defend ourselves from “fake news” and other misinformation that pervades modern communities. An adult citizen in the digital era must be competent not in the matter of detecting and confirming the reliability of news. He must understand the reconstruction of the reputational path of the information received, evaluate the intentions of those who disseminate it, and calculate the plans of the authorities confirming its authenticity.

When we find ourselves in a situation where it is necessary to accept or reject the information, we must ask ourselves: where did it come from? Do you have a good reputation at the source? What authorities trust her? What are the reasons I consider the opinion of these authorities? Such questions will help us to remain on a wave with reality rather than trying to directly verify the reliability of the information under discussion. In a hyperspecialized knowledge production system, it does not make sense to start your own investigation, for example, the possible correlation between vaccines and autism. It will be a waste of time, and our conclusions will most likely not be accurate. In the era of reputation, our critical assessments should be applied not to the content of information, but to the social network of connections that formed its content and gave it a certain “rank” in our knowledge system.

These new data constitute something like a second-order

epistemology . They prepare us for assessing and verifying the reputation of the source of information, for what philosophers and teachers need to prepare for future generations.

According to Friedrich Hayek’s

Law, Legislation and Freedom (1973), “civilization is based on the fact that we benefit from knowledge that we don’t have.” In a civilized cyber world, people need to know how to critically evaluate the reputation of a source of information, and to give new opportunities to their knowledge, having learned to properly assess the social rank of each information that falls into their cognitive field.