Hearing on a recent Facebook data leak incident in the US Congress allows us to make a variety of conclusions.

- For example, that the majority of representatives of the US legislature do not understand anything about the mechanisms of Facebook, not to mention the business models of this platform, which for thousands of years served as the engine of innovation in various sectors of the economy.

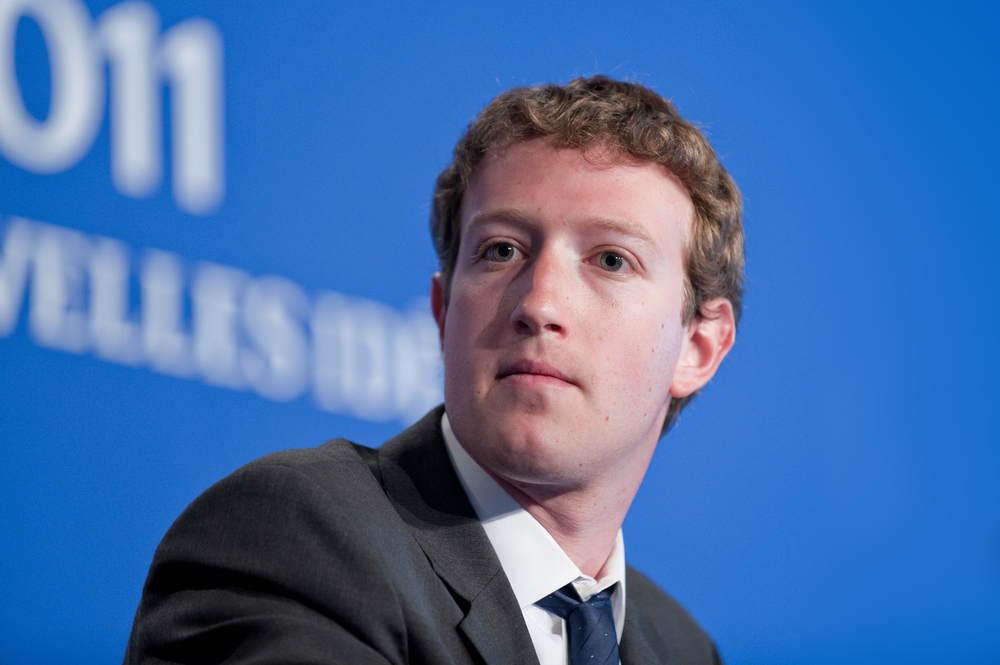

- That Mark Zuckerberg showed impressive restraint in the context of lengthy repeated questioning, which lasted two days and 10 hours, and made it clear that the legislators lacked the above understanding.

- That the one who has thought up to limit monologues and questions of legislators till 4 minutes should be awarded the Medal of honor. Those who managed to reduce them to 1 minute should generally be awarded the Nobel Prize.

- That the regulation of social media will be tightened, and this will lead to the emergence of overwhelming requirements for all new or small players, which will weaken their position in the market and strengthen Facebook's position.

- That the lawmakers decided to choose one measure for all large companies that use consumer data: now they have all become bad guys who are looking for ways to make billions at the expense of consumers.

However, the last point that has recently become central to all disputes about Facebook data leakage is of most concern.

The reason for concern is not that large players like Facebook should not pay for such serious mistakes. Of course they should, and Facebook will bear responsibility for this. After all, it is precisely for this that there are such bodies as the Consumer Protection Division of the Federal Trade Commission, not to mention lawyers specializing in class action lawsuits and regulators in other countries.

And not because all companies should be sensitive to the security and storage of personal data if they want the consumer - their main value - to come to them for the service again and again.

This concern is caused by the fact that the authorities are not willing to take into account the fact that all platforms are seriously different in their approach to obtaining and applying data. And not all of them behave like Facebook.

In particular, legislators in their attempts to cut one size fits all ignore the intentions of consumers using the services of these platforms. They do not take into account the difference between the policies and approaches of these platforms and the expectations of users from them.

This is the key idea underlying my annual

January material on promising trends that determine the development of payment and commercial ecosystems in the next few years.

In this article, I wrote that influential players in the payment and commercial areas understand how to use the context to monetize consumer intent without compromising user confidence, their data and expectations from the platform. It is for this reason that I called Google Search, Amazon, and other platforms like them, and not Facebook, the new driving forces of our world.

And now let's see why it is important not to throw the fruits of these information platforms into the rushing waters of the regulatory environment of Congress.

Evolution of the advertising platform

Less than 20 years ago, even before the advent of the modern digital, mobile, always connected world, the main sources of information were newspapers and television.

Then people read the daily newspapers to find out what's going on in the world. Their full content pages, among other things, contained ad units placed by companies hoping to interest the consumer, build a brand or stimulate purchases.

The same people sat in front of the TV to watch their favorite shows. Every seven minutes or so they were shown an advertisement aimed at solving the same problems - building a brand and stimulating purchases.

Of course, consumers read newspapers and watched TV not for the sake of advertising, but for the sake of content. Advertising only accompanied the main occupation.

Truly good commercials created the impression that the brand addressed consumers directly, although the best that brands could hope for was that people watching LA Law or CSI, or who read The Boston Globe and The Wall Street Journal represented an audience with more or less homogeneous interests and views on life. Thus, neither brands, nor publishers, nor networks could know for sure whether this advertisement helped increase sales. Hence the famous saying about the fact that it is not clear which of the 50% of the budget for advertising, newspaper or television, brings real sales. One way or another, any advertiser then realized that these were the best ways to reach out to a wide audience.

Advertising breaks also had another important purpose: they allowed to attract the attention of the consumer, and the right choice of content allowed to attract the right audience (soap operas during the day - mothers of housewives, financial news - business people).

The business model and dynamics of such platforms gave consumers the opportunity to watch TV for free and buy newspapers for only 25 or 50 cents. Advertisers paid for cheapness and affordability: they paid dozens and even hundreds of thousands of dollars to TV networks and newspapers for reaching the audience.

Before the advent of digital and mobile stores, the main shopping places were physical stores and malls. They were almost the only places where consumers could find the things they needed.

Moms collected children and went to the store to shop and to see what was there. Coupons, advertising brochures and signs in the store told about discounts and promotions. This advertisement was very helpful: it allowed at the right time to tell the consumer ready for purchase about her product.

Across the chest in a sea of digital exhaust

A modern fully digital, fully mobile world is replete with new digital intermediaries who want to attract the eyes of consumers in order to monetize the digital exhaust, which their interaction will leave behind.

And this digital exhaust a lot.

In July 2017, Domo, a business solutions and analytics provider,

estimated that 2.5 quintillion bytes of data are generated every minute in the world. The concept of “

data is a new oil of the digital economy ” has intensified the activities of top managers of companies, their advisers and investors. Now they use all possible tools and new technologies to search and monetize these intangible analogues of oil wells. Now, anyone without a source of income, the business seeks to make the interaction with consumers on various platforms can be turned into accompanying profits.

But the transition to fully digital and mobile interaction does not change the intentions of consumers or their expectations from the platforms they use.

The intention to share content, and not to give their data to someone else's use

Take, for example, Facebook.

From the very beginning, Facebook’s characteristic handwriting consisted in recruiting a critical mass of platform visitors, whose attention they could use to attract advertisers and monetize ads. Registration on Facebook strongly prompted the user to fill out a profile, which gave the company the opportunity to find out, among other things, such details of his personality as name, postal address, phone number, age, gender, school, employer, title, marital status. These data were supplemented with the growth of the user's social network, his likes, comments and content that he shared. When users watched the news feed of their friends, they were offered ads. The way it was presented was similar to a newspaper or TV advertisement, but this time the choice of its content depended on their likes and preferences.

In many ways, this experience was very similar to the experience of any other content platform with advertising support.

But at one point he changed.

The way to monetize views by selling advertiser access to users has led to cluttering up user-generated content by an excessive number of ad units. The news of friends and the content they share has become too difficult to search among sponsored posts, advertisements, and eventually even fake news. Brands, once captivated by the possibility of highly targeted shows, noticed that their signals stopped reaching large sections of the audience and changed tactics.

What consumers didn’t exactly expect during registration on Facebook or during its continuous use was that they would have to become part of a platform that would take all the personal data listed above and make it accessible to third parties without their permission. And the fact that these third parties will, again, without the permission of the users show them some content, as well as do other undesirable things with the collected data.

They also did not give their consent to tracking their activities using cookies during the moments when they were outside the platform. The majority of users did not even know how much of their personal information was available to other sites when they logged into them using Facebook Connect.

Over the years, Facebook has adjusted its policies to stop some of the wrong practices leading to compromising user data without their knowledge. Among other measures, it should be noted that third parties have limited access to the user's social contacts map and prioritized the content generated by them in the news feed.

The scandal with the leakage of data into the Cambridge Analytica system, appearing on the front pages of all publications raised a level of concern about personal information. Now there are questions everywhere about how and why personal data no longer even 87 million people, but all 2 billion users of the platform could be at the disposal of a third-party company without the direct or hidden consent of users.

There is a feeling that Facebook not only closed its eyes to the behavior of such offenders, but also ceased to take into account the intentions of users of the platform, namely their desire to share content with friends, view content shared by friends and receive information and advertising adequate to their interests, like this takes place on any ad-supported content platform.

The company has forgotten that its customers do not want third-party agents to enter them, who obtained their data without their consent.

Lost in Facebook and that visitors use the platform is not to help the development of commerce.

Brands are known to consider Facebook and its news feed as a natural place to place contextual ads. Nevertheless, the study, the results of which will be published by us soon, found that there is an inverse relationship between frequency of use, budget and level of satisfaction with contextual commerce and the use of Facebook as a platform for this type of commercial interaction with the client.

Intention to buy

Quite different is Google Search.

Every second, visitors create

40 thousand search queries in the Google search engine, which translates into 3.5 billion queries per day, or 1.2 trillion queries per year. These requests are caused by the desire of users to find an answer to certain questions: when is it time to pay federal taxes? Why does the weather deteriorate during the Boston Marathon for the past 10 years? Will spring ever come in the northeast?

And increasingly there are questions about where you can buy a particular product.

These questions demonstrate the intention of consumers to buy, as well as their expectation of receiving an answer with possible options within a few milliseconds. They know that they will receive a lot of offers in response, including the ad units paid at the top of the search results, displayed by retailers or brands, ad units displayed when entering certain keywords. After receiving the search results, consumers are free to decide whether they want to click on a particular result and make a purchase.

Google search uses the intentions of the consumer to find a suitable set of places in which the purchase of the desired product is possible. In this case, the search engine knows only where the buyer is, without owning and not needing any information that can help determine the identity of the person. If a consumer enters a merchant’s website that has connected to Google Pay, or pays a purchase through filling out a form in Google Chrome, then any user data known to Google is used to expedite ordering only after the user's permission. And of course, if the buyer wants to use other payment methods, he chooses the methods available from the merchant and makes payment with their help.

This process is very different from the Facebook approach.

The main reason why a consumer opens a news feed is the desire to find out how friends are doing, or to read the news, and not to buy a product. Consumers resort to search only when they are really interested in its results, and if advertising fits the search query, Google shows ads. Most search pages only show ad-related ads, if any. As for the Facebook news feed, on the contrary, it always shows ads.

Take, for example, Amazon.

When a consumer goes to Amazon to purchase something, the service also shows him a list of products that can be bought, including sponsored products, related recommendations and product reviews. If our consumer is an Amazon client, he will also see information about whether he bought this product earlier and will be able to buy it in one click or add it to the list of products for Dash buttons, if we are talking about products of regular use.

Amazon uses the consumer’s intention to find the product of interest to find the right product and vendor and to ensure its purchase on the platform. The company gives sellers the opportunity to conduct their business without providing them with consumer data, and retailers often criticize Amazon because of this position. But since Amazon entered the business of selling and selling goods, the company became directly interested in making customers happy with their purchases, and therefore really care about it.

And again, we see a significant difference compared to Facebook.

By clicking on the ad unit on the FacSebook and buying a product, consumers are unlikely to blame the social network if the purchase fails, because Facebook does not position itself as a commercial platform. At the same time, if a consumer buys something on Amazon and they don’t like the purchase or the thing breaks, they will blame Amazon.

Intention to share

There are many other platforms involved in the business of monetizing the intentions of the consumer.

The names of two such platforms recently hit the headlines.

Uber

announced that its application will soon become a transportation hub for consumers.

In addition to being able to find drivers and cars in the app, consumers will now have the opportunity to find and book tickets for local public transport, rent a bike thanks to a recent acquisition by the company of the rental service JUMP, and also find someone who wants to rent their car for an hour or a day. This is a response to the intention of the consumer to move around the city easily and conveniently.

Earlier, Uber Eats has already appeared in the Uber services, a $ 10 billion business that uses user location data and Uber account information to offer the best options for ordering food in local restaurants with payment and delivery via the Uber application.

To get all the benefits offered by these services, users only need to create a profile with the name, email and billing information. Adding to this the location of the driver and client, Uber, transforming the user's intention without unnecessary, worsening his impressions of the trip advertising, provides its convenient service.

The second company Zillow also recently got into the news bulletin,

announcing that it would use its very popular platform for buying and selling real estate and its reputation in this market to launch a home buying service for its subsequent resale. The market did not like this decision: Zillow shares fell by 9%, due to investors' fear that the company would have a conflict with realtors who actively use the service to publish their offers on this basis.

However, for Zillow, launching a new service is another way to monetize the consumer’s intent to find and buy a home by offering a convenient way to sell what he has now.

About the importance of intent

The late Supreme Court judge Thurgud Marshall once

wrote : “How good is your intention?” It was a rhetorical question, behind which was his own intention - to highlight the difference between what a person can say and the real intentions behind these words. Intention, he said, always floats to the surface, no matter how bad or good it is.

And this is a pertinent analogy in light of the recent debates about user data, which will probably not subside any time soon. The intention of consumers interacting with real and digital platforms is, in most cases, quite obvious. But about the intention of the platforms to say the same thing is not always possible.

It's time for us to eliminate this difference.