A 14-year-old press release showing the infamous engineer’s early dreams

GhostRider, a motorcycle without a rider, created by a team of engineers led by Anthony Lewandowski for the DARPA Grand Challenge competition in 2004Note Trans.: Anthony Lewandowski - American engineer, creator of automatically moving vehicles. He worked at Waymo, a division of Google, to create a mobile phone. After leaving there, in 2016 he founded Otto, a company operating in the same field. A couple of months later, Uber acquired the company. A year later, Waymo accused Lewandowski of stealing company confidential files containing key information on the operation of the systems necessary to create a mobile.

GhostRider, a motorcycle without a rider, created by a team of engineers led by Anthony Lewandowski for the DARPA Grand Challenge competition in 2004Note Trans.: Anthony Lewandowski - American engineer, creator of automatically moving vehicles. He worked at Waymo, a division of Google, to create a mobile phone. After leaving there, in 2016 he founded Otto, a company operating in the same field. A couple of months later, Uber acquired the company. A year later, Waymo accused Lewandowski of stealing company confidential files containing key information on the operation of the systems necessary to create a mobile.The fact that Waymo made her lawsuit against Uber over the leak of secrets related to the lidar does not mean that Anthony Lewandowski left the radar screens. The US Department of Justice can still accuse a former Waymo engineer of a criminal offense of stealing technical documents from a former employer. And then there is the question of what Lewandowski will do next: does he use his extensive experience with autonomous vehicles to launch another startup, and will he return to this area?

During his testimony last year, Lewandowski did not want his experience and plans to be studied. When Waymo lawyers asked him hundreds of questions, mostly about his activities in Waymo and Uber, Lewandowski took advantage of the

fifth amendment to avoid giving answers that could denigrate him. However, he was ready to talk about his other project: GhostRider.

“What project did you participate in the 2014 DARPA Challenge competition?” One lawyer asked, referring to the well-known competition organized by the Pentagon, with a prize fund of $ 1 million, where the creators of automatic vehicles competed and which launched all of today's industry. “The project was called GhostRider, it was a two-wheeled motorcycle,” answered Lewandowski. “He was the first of its kind, and, frankly, it was a pretty crazy idea.”

The creation of GhostRider Lewandowski a robot child prodigy, secured him a place in the subsequent DARPA Grand Challenge competition, and allowed him to create the first robot mobile for Google - later this step will make him a multimillionaire. In 2007, Lewandowski immortalized his role as a pioneer of robots,

donating a GhostRider to the Smithsonian National Museum of American History.

Lewandowski had

been interviewed many times, and he had already talked about his project. And yet the full history of GhostRider has not been told yet. For example, apparently, the project of an unmanned motorcycle that launched a career Lewandowski, generally lucky to get to the competition

DARPA Grand Challenge .

Our magazine has put together a piece of GhostRider history, both from new interviews and from those that were given while working on the project, as well as from other sources, which includes a press release 14 years ago - a brilliant white folder labeled GHOSTRIDER ROBOT on the cover - recently discovered in our edition.

Lewandowski first heard about the DARPA Grand Challenge competition when he was a graduate student in engineering at the University of California at Berkeley in 2002. He immediately decided that he wanted to race.

Brainstorming in the hot tub, Lewandowski and his friend, Randy Miller, gave birth to a bunch of ideas, including a non-motorcycle bike and a robotic loader. “But the idea of a motorcycle took shape when we drove back from the Grand Challenge conference, and a group of motorcyclists overtook us on the highway,” Lewandowski said in an interview last week.

The motorcycle, and at first it was a Honda XR, was easy enough to throw it in the back of a pickup truck, and so Lewandowski could lift it when it inevitably fell. This motorcycle also became one of the most inexpensive devices that participated in competitions from DARPA, since Lewandowski estimated the cost of a multi-year project at $ 100,000. He spent his money and also received funding from corporate sponsors and private donors.

"People transferred money through PayPal, a dozen from there, a hundred from here," he said, and added: "It was something like an early Kickstarter."

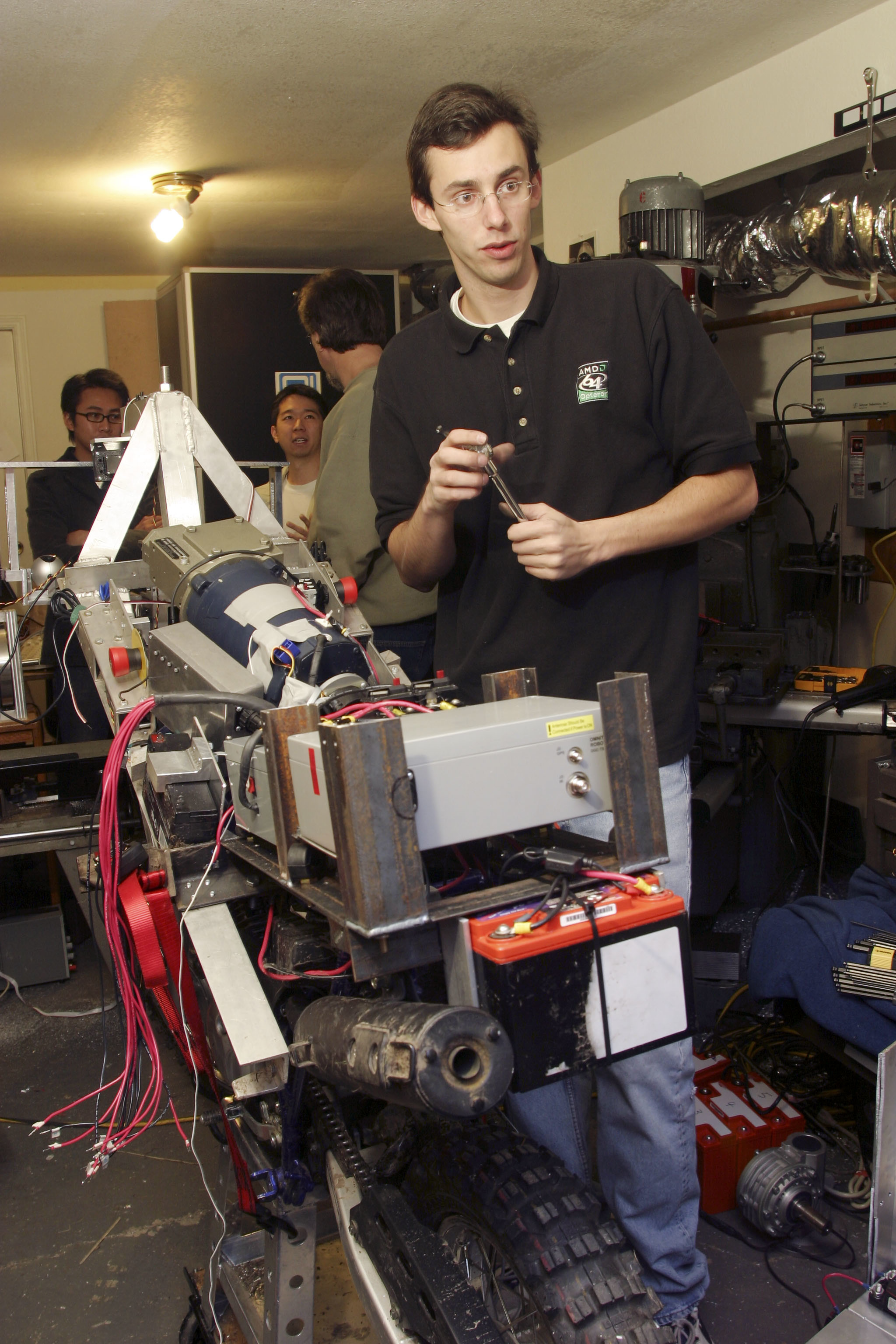

Lewandowski turned his tiny garage into the robotics laboratory, working on the project GhostRider

Lewandowski turned his tiny garage into the robotics laboratory, working on the project GhostRiderLewandowski began to assemble his robot-motorcycle in his garage near Berkeley, attracting several fellow students and engineers to his project. Volunteers were given a burrito as payment, and some of them eventually even moved closer to the project. The group decided to call the "Blue Team" as a friendly unit in military exercises. They called their robot Dexterit [Eng. dexterity - agility, speed, dexterity / approx. trans.].

One member of the Blue team, Bryon Majusiak, now involved in building agricultural robots, recalls how one day Lewandowski called him at 11 pm to ask for help to unload a motorcycle. “He was so impressed that I came and helped, and I started working with him constantly,” Majusiak recalls.

The first task of the Blue team was the installation of servomotors for gas, clutch and brake control. DC motor and worm gear worked with handles. Lead-acid battery powered electronics. Lewandowski tried a couple of Honda motorcycles, but then he stopped on the Yamaha 125 for the first Grand Challenge. The final motorcycle of the GhostRider was the Yamaha 90 children's

pit bike , chosen for having an automatic clutch, which Lewandowski called “salvation”.

After installing mechanical controllers, the Blue team was faced with the most difficult task. “In order for the car to move along the road, you need a little gas and not to steer, and it will go,” wrote Lewandowski in his testimony. “To get the bike to go forward, you must first create a bunch of technological stray that simply allow it to go straight.” He added: “It was difficult to create a balancer before it was possible to begin testing navigation systems and optical recognition.”

At some point in early 2003, after an agonizing development, Lewandowski recalls, as he told his team, that if they could not get Dexterit to go a mile until next Sunday, he would abandon the project.

But then he had a breakthrough, he came up with an elegant solution for the inextricably linked problems of balancing and turning. Instead of shifting the weight for balancing, as a person does, the Blue team realized that just steering the Yamaha motorcycle in the direction of tilting could restore balance.

“Counter-steering creates centripetal acceleration, which leads to the appearance of a rotational moment directed in the other direction,” Lewandowski told me. “And you are just balancing to and fro to go straight.”

To rotate the bike sent along the curve, keeping the steering wheel straight. In the 2003-2004

video , you can see an early version of a motorcycle that balances itself while standing still on the road. In a later

video, its advanced version rides around the lawn.

Although the idea itself sounds simple, it took months for the Blue team to achieve a smooth, human-like ride. Lewandowski says they dropped the bike a hundred times.

A technical paper from the 2004 competition reveals the details that the main sensors of the motorcycle were optical cameras with a range of up to 40 m. A pair of monochrome webcams looked forward, scanned the space for moving obstacles, and one color camera recognized the road. An on-board computer based on an AMD Athlon 64-bit CPU and with 512 MB of memory was capable of processing one frame in four seconds.

Cameras were mounted above the front wheel on a gimbal gimbal stabilizer, and another device with a gyroscope and inertia measurement provided orientation and acceleration data. Optical converters tracked the steering angle and speed, and GPS - the location of the motorcycle.

The team planned to take a set of route points - which DARPA issued shortly before the race - and process them with the help of a specially written application “to increase the density of route points and provide a more dense route to the device”. The motorcycle should be based on this data and be oriented in the desert, using cameras for detecting stones, holes and other devices.

“In fact, a lot of people collected different things and watched what works from this,” said Lewandowski. He hoped to install a 77 Hz mechanical scanning radar, but could not provide him with power. “I received a discharge of ten times in one day, trying to figure out where there was a short in this device,” he recalls. “We could not get it to work - and we did not try lasers.”

Many components were provided by manufacturers and sellers under sponsored agreements.

Hobby Engineering , the robot kit vendor, was involved in this project when Lewandowski called its founder, Ella Margolis, at 3 am. “Lewandowski was amazed when they answered the call,” Margolis wrote in a press release during the competition. “He did not expect an answer, much less real help, but he was desperate enough to try.”

A few hours later, they met in the demo room of Hobby Engineering, where Margolis passed several microcontrollers and offered help in finding bugs so that Lewandowski could have time to start demonstrating the devices.

No one in the team worked on the project anymore than Lewandowski, recalls Randy Miller, who now works

as an engineer and developer : “He could work all night and plow for two or three days without stopping, without sleeping.”

As the competition approached, Lewandowski pondered more and more what could happen if the Blue team copes with the weekly qualification tests in California and actually gets to this noticeable (and potentially profitable) event. Lewandowski changed the stupid name of Dexterit to the more memorable GhostRider and compiled a press release, where was his own profile (in which he called his idol Bill Gates), slides with the presentation and letters from such sponsors as

Agilent and

Crossbow Technology . In 2004, he also founded Robotic Infantry Inc. [robotic infantry] to "explore possible military and commercial applications of this technology."

According to the presentation slides, the next steps of the company were to include the modeling of GhostRider components in 3D, the creation of an electrical model from carbon, the improvement of sensors and software. By 2007, Lewandowski hoped to give a product suitable for driving on roads, and ready to “consider acquiring technology and explore potential opportunities for investment or an IPO.”

The blue team worked on GhostRider until the last minute, and added a remote emergency shutdown, which DARPA insisted on, just a few days before the start of the competition. “Like the other teams participating in the competition, it was very difficult to get GhostRider in time,” Lewandowski said. - Our priority was to first get him to drive, and only then stop. The stop was not a problem for us: if something did not work, it just fell. ”

On March 8, 2004, 25 teams arrived at a California racing track near Los Angeles for the qualifying race. DARPA has marked at a distance of 2.2 km of obstacles that will meet the machines in a real race - hills of mud, pits, fences and a pit of sand. Machines needed to pass a security check and complete at least two races over the distance.

Lewandowski prepares GhostRider for the race, March 13, 2004

Lewandowski prepares GhostRider for the race, March 13, 2004The Grand Challenge was about to allow 15 of the fastest and most capable cars to compete, and GhostRider faced a battle with teams that had good funding — for example, from Stanford and Carnegi-Melon universities, Caltech and the freight company Oshkosh Truck Corporation.

“In the first year we passed the qualification,” Lewandowski said in his testimony. “And out of the 109 teams that submitted the application, only 14 passed the qualification, including us.”

But how exactly GhostRider turned out to be in competition is a bit incomprehensible. The blue team was supposed to make the first race on March 9, and their unique two-wheeled version attracted a large crowd of spectators. Unfortunately, the Los Angeles Times wrote that on that day GhostRider fell on its side, driving only 4.5 meters. The next morning, GhostRider was again in the ranks, but again could not make the race, as written in

the DARPA news . Lewandowski told DARPA in general that the Blue team ceased its attempts. And GhostRider was not the only one - many teams hardly forced their cars to drive without colliding with obstacles and without moving off course.

March 11, the last day of qualifications, 38 teams tried to complete the course. Blue team was not among them. By the end of the qualification, seven cars were able to drive at a distance at least once, and another eight were in the category of "partially completed" race, as DARPA determined them. This is exactly the 15 teams that DARPA wanted to allow directly to the races on March 13th.

Fourteen of the fifteen teams appeared in time for the race. One, Rover Systems, an innovative SUV with a low center of gravity and steering all four wheels, did not make the list, despite the fact that it drove some parts of the course twice. Instead, DARPA

decided to include GhostRider in the list , which showed little progress on its first day.

Lewandowski explained this by saying that they "deserved their place" in the race. “We have shown that we can force the motorcycle to leave the gate, turn around, drive straight, and crash into a fence,” he said. Perhaps the project was helped by the fact that Lewandowski made the motorcycle ride in a circle in the parking lot next to the qualifying race.

Whether the reason was a successful impromptu or Lewandowski’s ability to attract attention, but GhostRider was able to participate in a 230 km cross-country race between the cities of Barstow in California and Las Vegas in Nevada for a prize of $ 1 million.

GhostRider reverses after slamming into the wall on the 2005 qualifying round at the DARPA Grand Challenge. As a result, he missed the final race.

GhostRider reverses after slamming into the wall on the 2005 qualifying round at the DARPA Grand Challenge. As a result, he missed the final race.Lewandowski soberly assessed the prospects of GhostRider. “We didn’t have a chance to win, we wouldn’t even have enough gas to drive the whole distance,” he said. “But we hoped to at least get out of the gate, go through the first turns, and then, probably, drive into some tree in 100 meters.”

But when the starting gun sounded, GhostRider could not even beat his personal record of 4.5 meters. Instead of rushing to the desert with a buzz, it just fell. His competition ended in a few seconds.

“It’s quite difficult to drive a motorcycle by hand when it tries to balance itself — it resists,” Lewandowski told me. “So we turned off stabilization when we were driving the bike, and then forgot to click the switch to turn it on again.” It was a shame.

Shame or not shame, but the participation of GhostRider in the first race of the Grand Challenge made the name of a 23-year-old engineer. Since no car reached the finish line that year, DARPA invited all the finalists to come back and take part in the next race of 2005, this time for a prize of $ 2 million.

GhostRider again failed to complete the qualifying race, although this time DARPA did not include it in the main race. It was won by Stanley, a robo-mobile based on the Volkswagen Touareg crossover, created at Stanford University by a team led by Sebastian Tran.

From left to right: Anthony Lewandowski, Sebastian Tran and Chris Armson with one of Google's first robotic vehicles.

From left to right: Anthony Lewandowski, Sebastian Tran and Chris Armson with one of Google's first robotic vehicles.Tran was filled with sympathy for Lewandowski, and after the races gave him a tour of the laboratory at Stanford. In 2006, Tran invited Lewandowski to help him with the VueTool camera layout project, which attracted the attention of Google, which hired the entire VueTool team the following year to develop its StreetView system. For a couple of years, Lewandowski and Tran created the first robot for Google, and the rest is history.

Lewandowski is not ready to talk about what he will do next. But it is unlikely to be associated with motorcycles. He laughs when I ask him if he thought about returning to the idea of an autonomous motorcycle. “I don’t think this is a good platform for autonomous vehicles,” he says. “This is a good thing for training, and it can be made to work, but there is no need for extra complexity, and it is quite difficult to transport cargo.”

“It would be interesting to remake GhostRider purely for fun,” he adds. “But it’s not so much connected with robots.”